Summary

Here is our review of Phaidon’s new biography of the Bauhaus founder and architect Walter Gropius—let’s dive into his life and his ever-lasting legacy.

About the Authors

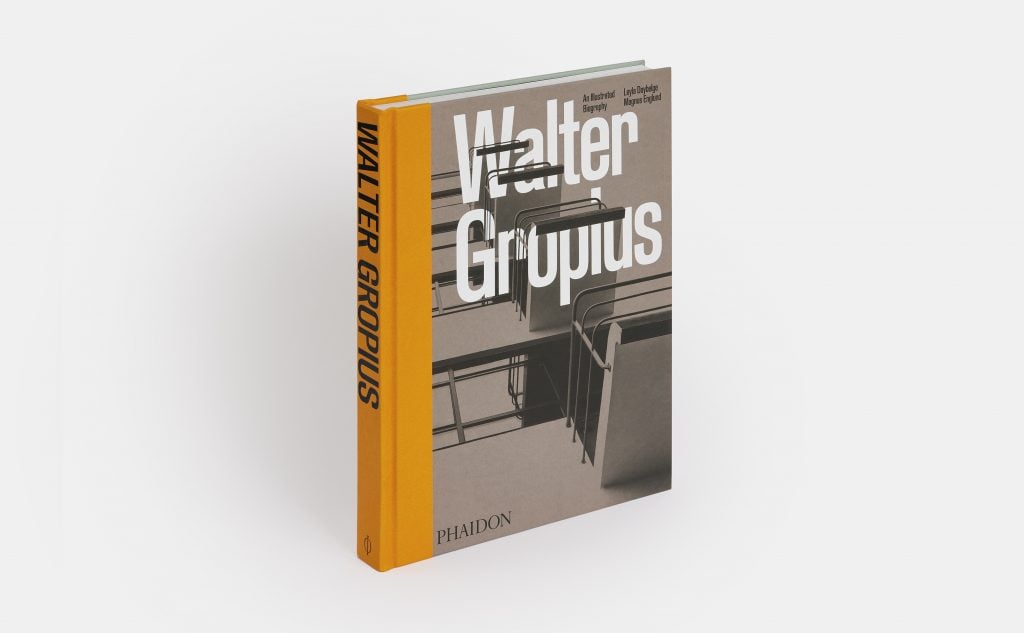

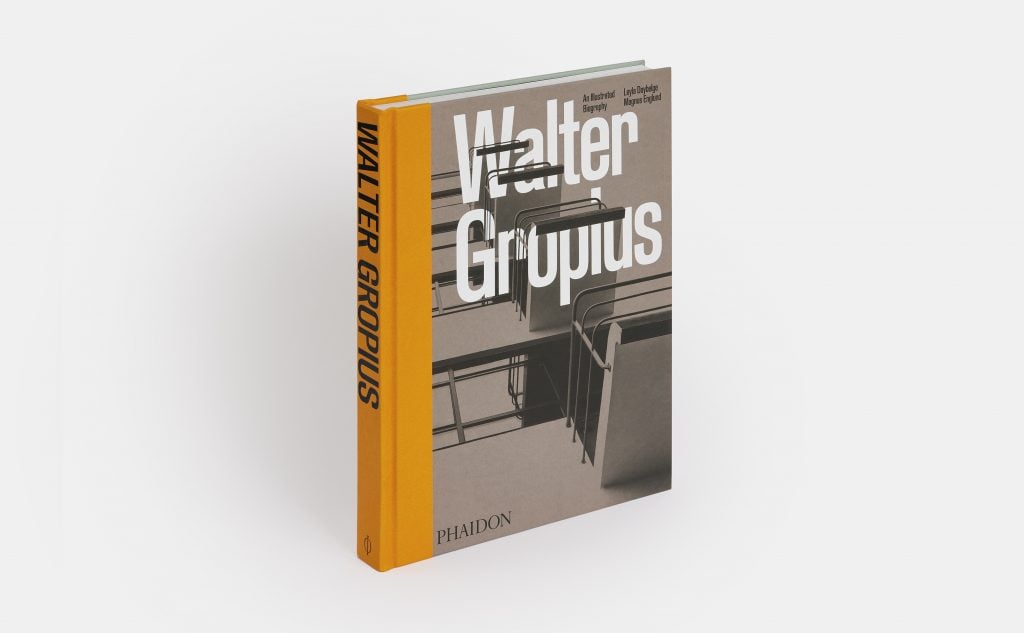

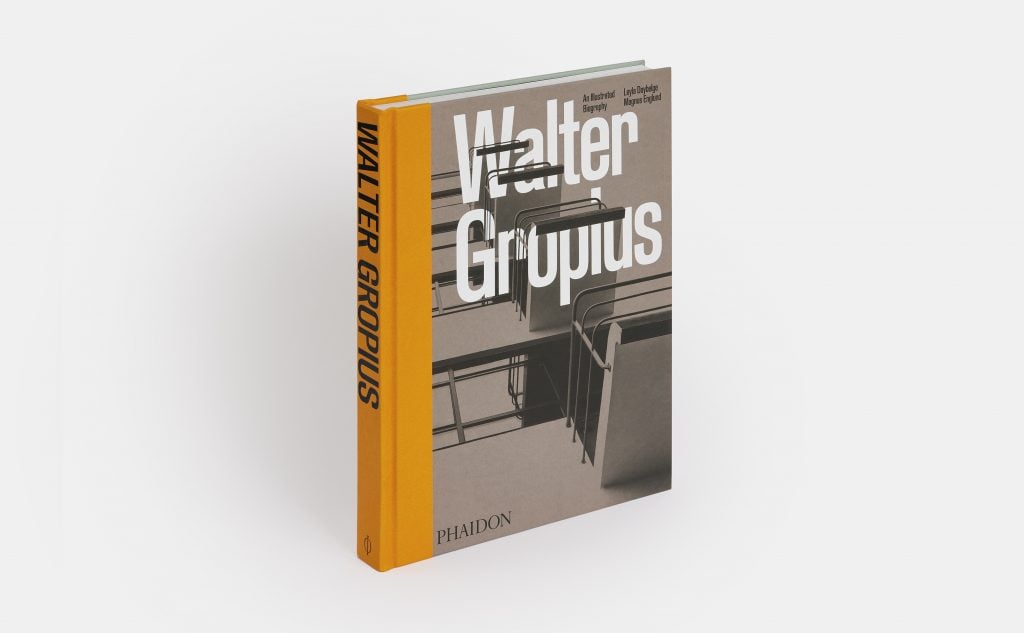

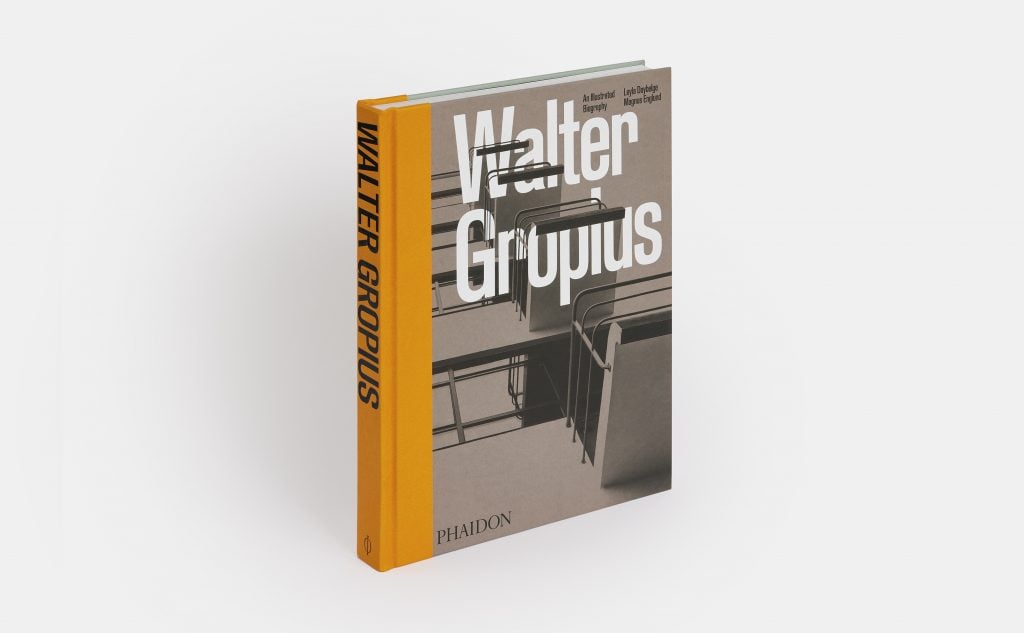

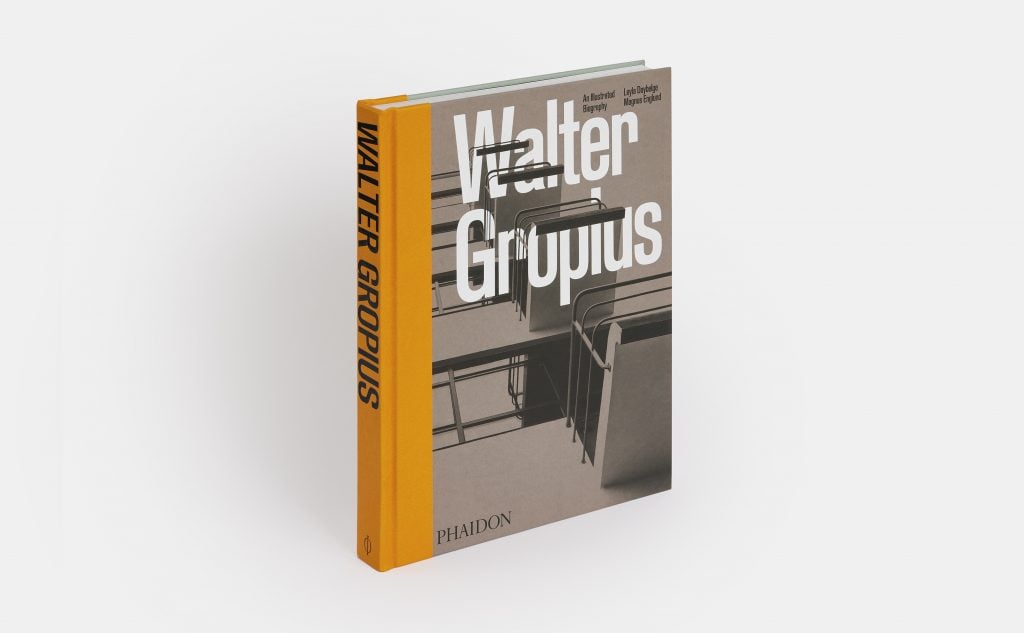

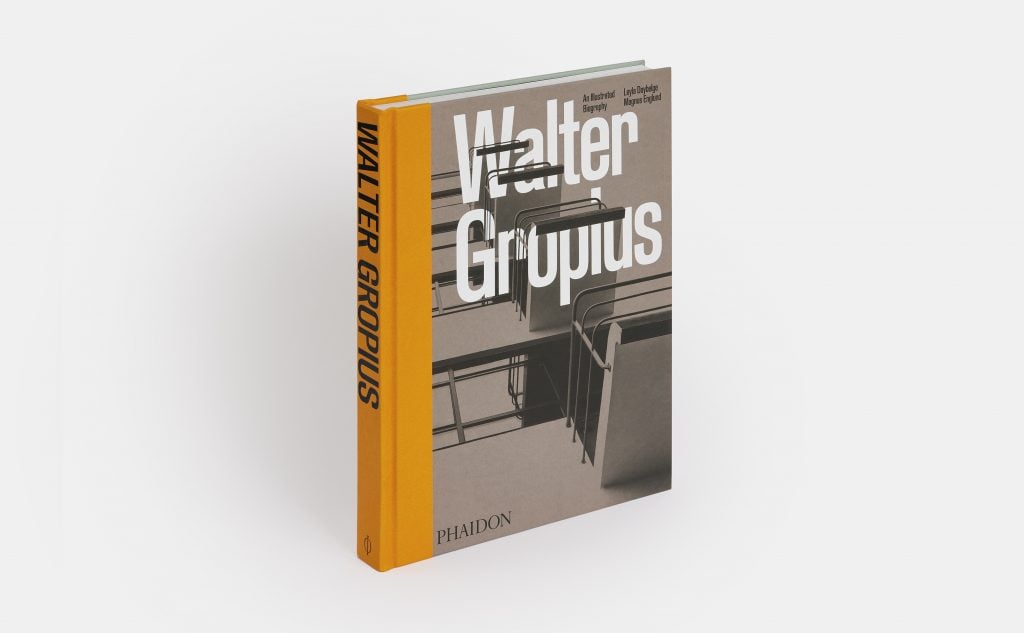

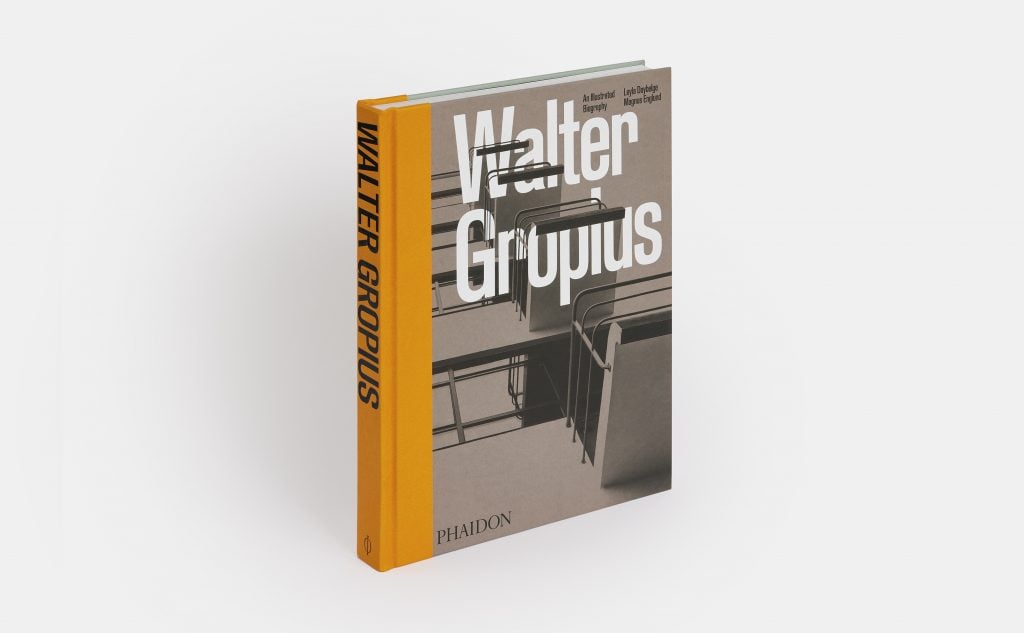

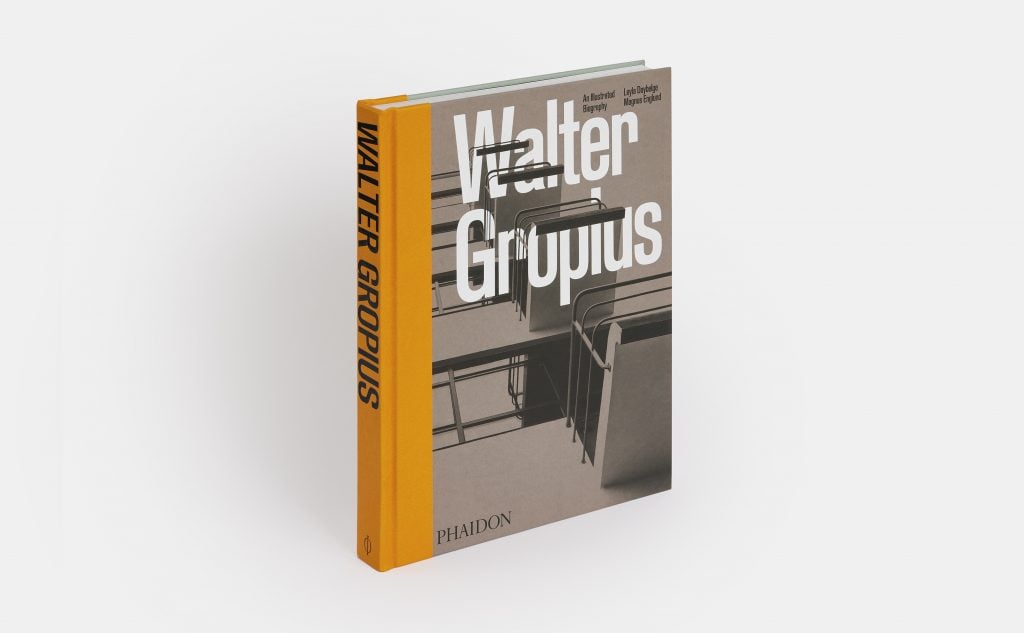

The co-authors, Leyla Daybelge and Magnus Englund, specialize in design and Bauhaus. They have previously released Isokon and the Bauhaus in Britain about three key figures of the international Modern movement—Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, and László Moholy-Nagy—and their life and work in London upon fleeing Nazi Germany in the 1930s. Now, they present a work dedicated solely to Gropius’ life: it is the first comprehensive and illustrative biography of the Bauhaus’ founder, featuring more than 375 illustrations and pictures: letters, sketches, drawings, photographs, brochures, and telegrams.

Walter Gropius: An Illustrated Biography by Leyla Daybelge and Markus Englund. Phaidon.

The Retelling of Gropius’ Life

The book tells the story of Walter Gropius’ life thoroughly, from the days of his early childhood in Berlin, Germany, to his very last days in Boston, MA, USA. It also divides his life into three stages based on the place where he lived: he was a young architect and the founder of the Bauhaus in Germany, an exile in England, and then, in the USA, an educator and an architectural elder statesman. These lives were shaped by the current circumstances in which he had found himself—be it war, ambition, or money—and he in turn shaped the 20th century. These stages cannot be separated nor discussed separately, as I believe what was unique about Gropius can only be spotted accurately portraying his entire life, which was the authors’ intention.

Walter Gropius: An Illustrated Biography, Chapter 7: USA and the World, 1952-1969, by Leyla Daybelge and Markus Englund. Designed by Felix Müller and Karl Oskar Blasé. Courtesy of the publisher.

Master of Modernism

Telling a life story of a master of modernism is not an easy task: in this biography, the reader firstly gets introduced to Gropius as a little boy and then an aspiring architect in Germany who has yet to master his craft. Gropius had clear, revolutionary ideas about what architecture should be like and, in turn, became one of the founders of the Modern Movement: he believed that modern architecture should make the most of industrial materials and use new forms, thereby detaching itself from the past and the “canon.”

Walter Gropius, Spain, circa 1907. In: Gropius: An Illustrated Biography of the Creator of the Bauhaus, Reginald Isaacs, Bullfinch Press, 1991. Courtesy of the publisher.

In 1907, Gropius received a substantial inheritance from a great-aunt. He left the Technische Hochschule without completing his examinations and spent a year traveling around Spain with his friend Helmuth Grisebach.

Modernist Architecture According to Gropius

Gropius’ architectural manifesto was clearly expressed in the Fagus Factory building, his first serious architectural commission, and therefore one of the first modern builds he designed (together with Adolf Meyer) in 1911. It was commissioned by Carl Benscheidtm, a businessman and owner of the Fagus, who would remain his client until 1925.

Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer, Fagus Factory, 1911-1914, Alfeld, Germany. Photograph by Edmund Lill via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

It was the first time Gropius could put his theory into practice and break from traditional design philosophy, which he had to endure before while working under Peter Behrens. Although both of them were interested in industrial design and architecture, Gropius strived for authenticity: he believed that the exterior design should reveal the construction elements. The Fagus Factory was a complex of many buildings serving different purposes, so in order to make the design consistent, Gropius used yellow brick and raised the dark brick base to 16 in (40 cm) high.

Walter Gropius (far right), Peter Behrens’ Babelsberg office, near Potsdam, 1908. Picture credit: C. Arthur Croyle Archive. Courtesy of the publisher.

As an assistant in the office, Gropius worked alongside Mies van der Rohe and his future architectural partner, Adolf Meyer. Le Corbusier joined the Behrens office in 1910. Left to right: Mies, Meyer, Max Hertwig, Bernhard Weyrather, Jean Chandler and Gropius.

Its façade had become iconic for modernism in the following decades—Gropius used internal concrete columns in its construction to free the facade. From brick piers, he suspended iron frames with huge curtains of glass panels. The fully glazed exterior corners gave the building a lot of natural light and a sense of openness. The biography thoroughly studies Gropius’ actions throughout his design process, portraying him not as a “Modernist giant” or “an icon”, but as a simple craftsman with revolutionary ideas. Furthermore, the reader has the chance to examine him not as an architect, but also as a son, husband, student, and coworker, as the book dives into Gropius’ personal life.

Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer, Fagus Factory, 1911-1914, Alfeld, Germany. Bauhaus Kooperation.

Art and Design: Bauhaus

Gropius’ greatest legacy is probably his impact on art and design as a whole. It all happened in 1919 when he founded the Bauhaus, a revolutionary school of art, design, and architecture.

Design came into being in 1919, when Walter Gropius founded the Bauhaus at Weimar. This first school of design did tend to make a new kind of artist, an artist useful to society because he helps society to recover its balance.

Design as Art.

Bauhaus’ core objective was to unite all the arts: architecture, sculpture, painting, and design. Gropius’ curriculum taught artists how to create useful and beautiful objects that would reflect the spirit of the 20th century, the modern times. By combining elements of fine arts and design education and unifying them, Bauhaus produced multi-skilled graduates that shaped modernity as we know it today.

Not only did Gropius assemble a world-class teaching faculty (Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Oskar Schlemmer), but he is also responsible for their students, Modernist giants such as Marcel Breuer, Anni and Josef Albers, Gunta Stölz and Marianne Brandt.

Woman wearing an Oskar Schlemmer mask sitting on Marcel Breuer’s Wassily Chair, ca. 1926. Photo by Erich Consemüller. Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin. © Dr. Stephan Consemüller.

Beyond Bauhaus?

However, Gropius’ life should not be confined to founding Bauhaus and its principles, which this biography explicitly emphasizes. He had to leave the school as a director in 1928 because of the growing tension of right-wing political forces and the unfavorable public opinion, spending some years in Berlin until 1934, focusing on low-cost, high-rise architecture, which became his fruitless main goal.

His next, albeit short, life was ahead of him: he lived in London from 1934 to 1937 as a celebrated, yet impoverished architect: his lectures and presence ultimately led to mobilizing modernism in Britain and left a mark in British teaching of architecture and design.

Walter Gropius and Maxwell Fry, The Wood House, 1935-6, Shipbourne, Kent, UK. Featured in Country Life, 17 July 1958. Courtesy of the publisher.

The article stated that it is one of the very few modern 1930s buildings that had stood the test of time.

The last stage of his life was spent in the United States where he finally got to be recognized: he became the head of the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University and he played a major role in popularizing the so-called “International style”, although personally, he preferred the name “modernism”. Once again, he was responsible for a new generation of skillful architects, including names such as I. M. Pei and Philip Johnson. To further pursue his architectural goals, Gropius joined The Architects Collaborative (TAC), where he continued to win commissions.

Drawing of the north elevation for the Pan Am Building, New York. In The Architects Collaborative: Process Architecture No.19 TAC, The Heritage of Walter Gropius, October 1980. Courtesy of the publisher.

Soon, however, modernism was doomed to fall from grace, and Gropius became aware of the problems related to the rapid increase of high-rise architecture, something he strongly advocated for before. Conceived as a solution to the chaos of the rise of population, the endless iterations of prefabricated housing proved to challenge Gropius’ ideas and beliefs.

Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer, entry for Chicago Tribune Tower Competition, 1922. Picture credit: Harvard Art Museums / Busch-Reisinger Museum, Gift of Walter Gropius, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, BRGA.10.5. Courtesy of the publisher.

Nevertheless, there is no doubt that Walter Gropius was one of the most impactful people of the 20th century. This book explores all of the contradictions throughout various stages of his life, painting a picture of his existence not only as an architect and founder of the Bauhaus but also as a coworker, teacher, and friend. Through a rich selection of illustrations, documents, and personal letters, the reader gets the chance to dive into Gropius’ world: it is not always pretty, it is filled with personal tragedies, war, political tensions, and financial loss.

Walter Gropius: An Illustrated Biography, Chapter 7: USA and the World, 1952-1969, by Leyla Daybelge and Markus Englund. Courtesy of the publisher.

Clockwise from left: Walter and Ise visiting Britz-Buckow-Rudow in Berlin, June 1968; Drawing for the community center at the Britz-Buckow-Rudow development; Drawing for the shopping street at the Britz-Buckow-Rudow development.

What remains is a portrait of a resilient man who endured all of this and never lost hope nor ambition and strived to realize his vision; a man who was like a magnet for people, maintaining lifetime collaborations and friendships. There is no denying that he was a man of the great oeuvre – he was an architect, but he also designed trains, teacups, cars, and furniture. What one finds in his biography is not only related to modernism, it is related to a passionate, sophisticated man whose legacy should never be forgotten.

You can get your own (visually stunning!) copy of Walter Gropius, An Illustrated Biography by Phaidon on their website.