Before becoming a notable painter of American Realism, George Bellows (1882–1925) was a six-foot-two-inch (1.9 m) standout basketball and baseball player at Ohio State University. He attracted attention from the Cincinnati Reds, but traded in his bat for a paintbrush and moved to New York City in 1904 to study under renowned painter Robert Henri. Still, sports remained of high interest.

As part of the Ashcan School—a group led by Henri and including George Luks, William Glackens, and John Sloan—Bellows and his compatriots showed the coarse reality of everyday life. In addition to painting, many of the Ashcan artists worked as illustrators for newspapers and magazines. This influence can be seen in the narrative boxing paintings.

The Early Boxing Paintings

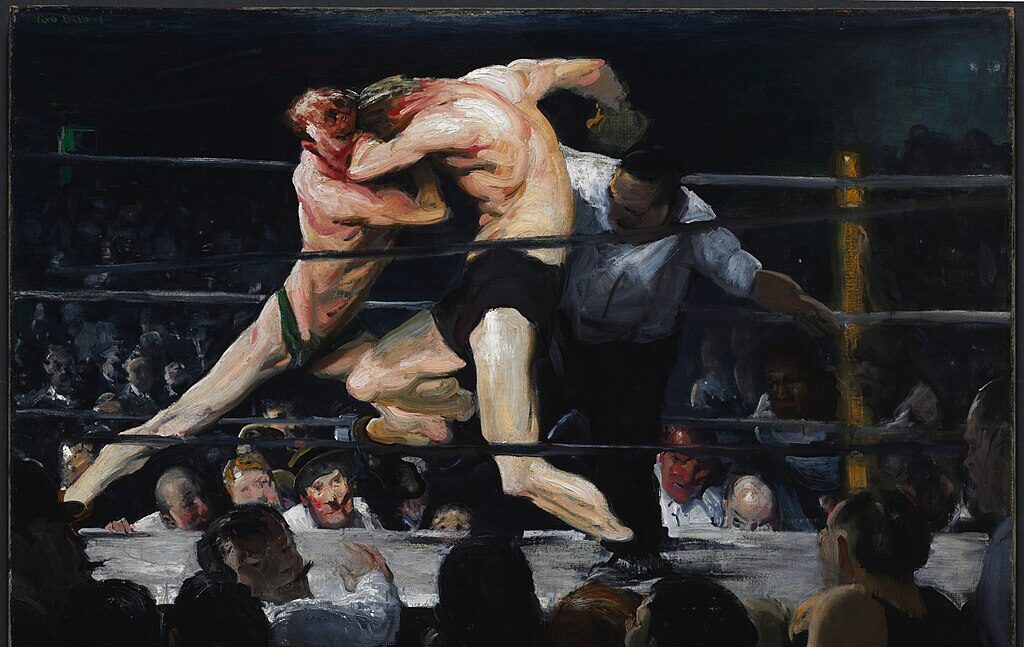

When Bellows arrived in New York, boxing enjoyed both wild popularity and shaky legal status. Bellows’ studio stood across the street from Sharkey’s, a boxing bar and the setting for Club Night (1907) and Stag at Sharkey’s (1909). Though dated years apart, they were likely painted around the same time. Both make use of dramatic lighting that accentuates the seedy nature of the spectacle and highlights the lean muscles of the fighters. Stag at Sharkey’s however, is painted more loosely, with longer brushstrokes matching the action of the fight.

During this time, a legal loophole allowed bouts between members of athletic clubs, so a bar like Sharkey’s would form an “athletic club” and offer one-night memberships to its fighters, hence the painting titled Both Members of this Club. Like Stag and Sharkey’s, long brushstrokes accentuate dynamic movements. However, in this work, open-mouthed, clown-like grins on the spectators harken back to the cartoons Bellows drew for various publications in his college days.

Adding to the taboo of the event is that one of the fighters is Black during a time of controversy around segregation in the sport. In his boxing days (1893–1904), club owner Tom Sharkey refused to fight Black athletes. Jack Johnson became the first Black Heavyweight Champion in 1908, and when he beat the white fighter James J. Jeffries in 1910, race riots broke out in several U.S. cities. In 1913, bouts between Black and white fighters were outlawed in New York state.

The Later Works

By the 1920s, new laws took boxing out of underground clubs to mainstream venues. Bellows continued to cover the sport through drawings and lithographs, and these works led to his later boxing canvases.

Introducing John L. Sullivan is based on a lithograph Bellows made while covering the Dempsey-Carpentier fight for New York World, and depicts the practice of honoring retired fighters before a bout.

Ringside Seats is based on a drawing done for the short story Chins of the Fathers, published in Collier’s in 1924. However, Collier’s brash cropping caused Bellows to file a lawsuit that was left unresolved after his death.

On assignment for the New York Evening Journal, Bellows was seated in the press box for the Dempsey versus Firpo fight at the Polo Grounds. The wild fight lasted only about four minutes, yet sent the fighters to the mat a combined 11 times. Bellows recorded the dramatic moment when a Firpo blow sent Dempsey flying out of the ring and nearly on top of Bellows.

Just one year after completing Dempsey and Firpo, Bellows died unexpectedly of a ruptured appendix at age 43. Some of the greatest American artists at the time served as pallbearers including Robert Henri, John Sloan, William Glackens, and A. Stirling Calder (father of Alexander Calder).

In his short life, George Bellows created some of the most enduring images of 20th-century America. His boxing paintings, a mix of blood and beauty, remain his most thrilling and recognizable.