Claims for the return of cultural objects have shed light on new narratives linked to national treasures. These accounts not only describe how the artifacts were looted and brought to European museums and collections during the colonial period; they also reveal a persistent reckless and arrogant attitude among Western people towards the cultures and nations who created these cultural treasures. According to some Norwegian and international researchers, the field of culture is still characterized by colonial thinking and practice. This also applies to the debate surrounding the Schøyen Collection, owned by the Norwegian collector Martin Schøyen.

Origins of the Collection and First Claims for Its Return

Parts of the extensive Schøyen Collection have been highly disputed over the past two decades because of unclear ownership of several items. Recently, a report from the Museum of Cultural History in Norway concluded that parts of the Schøyen Collection must be returned to Iraq because the objects were taken out of the country illegally. Iraq, since 2019, has been searching for objects from ancient Mesopotamia. The most valuable artifact, a floor plan of the mythical Tower of Babel, is said to be worth several million Norwegian kroner. According to the experts behind the report, there is no documentation that the objects were taken from Iraq legally. Schøyen has constantly denied Iraq’s demand for the return of the artifacts, even though he has been unable to provide clear documentation. Instead, the collector claims that Iraq has not proved that the objects were unlawfully removed from the country. The most startling thing in the report is that experts have established that many of the items in question were acquired through notorious dealers and smugglers.

Schøyen’s Rationale

Self-justification is a key element in current debates about the return of cultural heritage items. A much-used argument is that by bringing other countries’ cultural heritage to the West, Western collectors have preserved the objects for posterity; had they remained in their country of origin, these objects would probably have rotted away. During the past two decades, while the debate surrounding the Schøyen Collection has been ongoing, both the collector and several of the researchers associated with the collection have repeated this well-rehearsed argument, and tried to appear as protectors of “world heritage”. Scholars like Mark Horton, a professor of archaeology, believe the latter argument is rooted in racist attitudes from the past, that local people cannot be trusted to preserve and manage their own cultural heritage. This viewpoint is also common among the general public. In connection with the publication of the Schøyen report, I published a chronicle about the case. On the Facebook page of the magazine Agenda.no, we could read comments like: “Norway should certainly not help Iraq gain control over more of the world heritage. Get your country in order, then we’ll get back to it.” On the other hand, it is interesting how Schøyen expresses enormous pride in having secured the unique cultural treasures: “The Schøyen Collection thus crosses borders and unites cultures, religions and unique materials found nowhere else.”

Western Museums’ Refusal to Return Looted Objects

Most Western museums still refuse to negotiate the return of cultural heritage looted by colonialists or illegally transported by missionaries and collectors. A classic example is the British Museum which to this day refuses to return the Parthenon Marbles, also known as the Elgin Marbles, to Greece, or the Rosetta Stone that was removed by British Imperial forces in 1801 and which Egypt demands back. Schøyen has responded similarly. When the Norwegian National Authority for Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime (Økokrim) seized the disputed objects in the Schøyen Collection, the collector stated that “there is no basis for Iraq’s demand for return” and demanded the items back after three weeks. After the Schøyen report concluded that the objects were acquired illegally, probably looted from Iraq in the 1980s and 1990s, and must be returned, Schøyen, through his lawyer, not only refused to meet Iraq’s demands, he also attacked the experts behind the report and the Ministry of Culture that initiated it. Schøyen’s lawyer believes that “the current provisions on return cannot be given retroactive effect for items acquired before January 2007”. In other words, even if it can be confirmed that the objects were probably looted or stolen and smuggled out of the country, Schøyen will not return them to their country of origin.

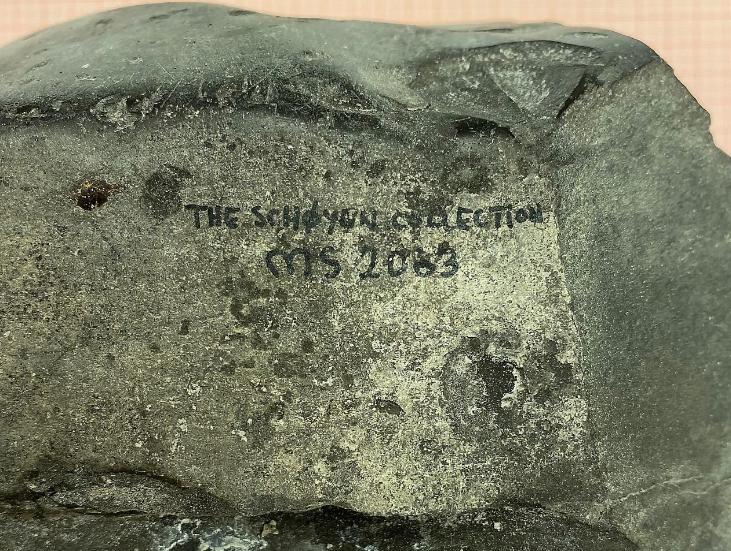

Another key feature of the claim for return debate is the disrespect shown towards local people’s traditions, religions, and cultural assets. The Schøyen report reveals how recklessly some of the objects in the Schøyen Collection have been treated. According to the report, several objects that originate from ancient Mesopotamia and are part of Iraq’s cultural heritage, have been cut down with modern machine tools. Some objects have been inscribed with ink, while others have been destroyed due to poor preservation. The experts conclude that Schøyen and his researchers have been directly involved in the irreparable damage and destruction of Iraq’s cultural and historical objects.