Read the story of Beata Beatrix by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, one of the key members of the Pre-Raphaelites movement. Discover the fascinating meanings of the symbols that the painter incorporated into this portrait.

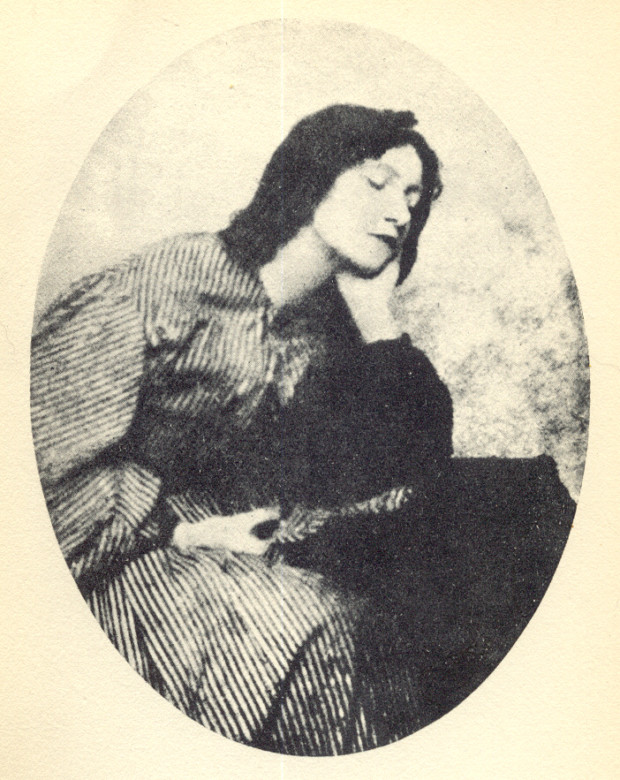

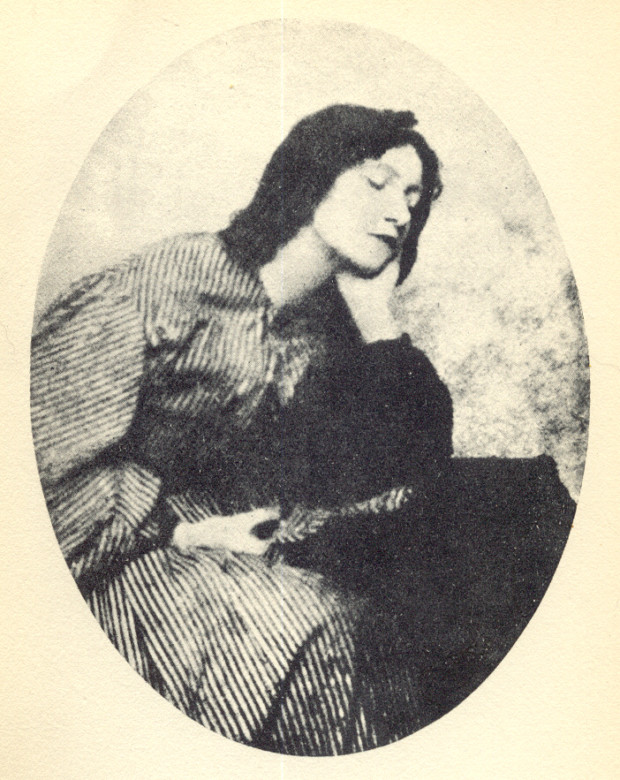

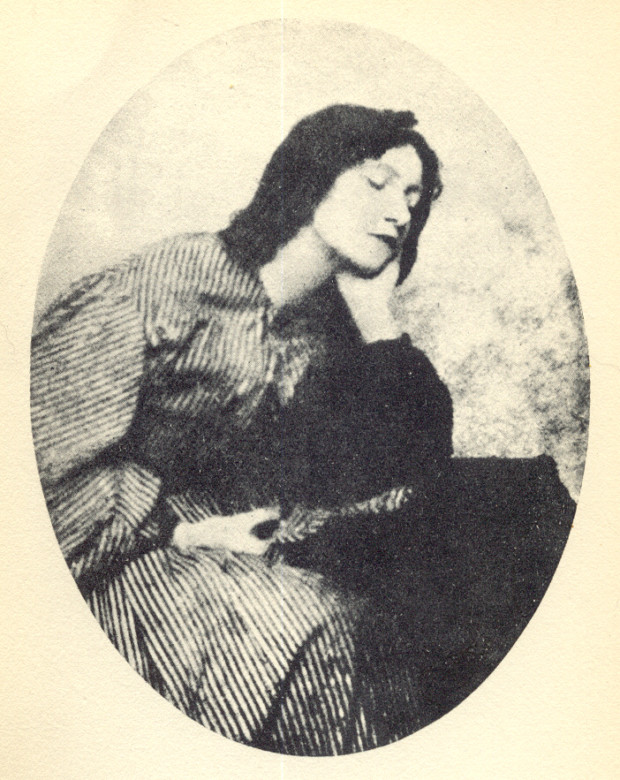

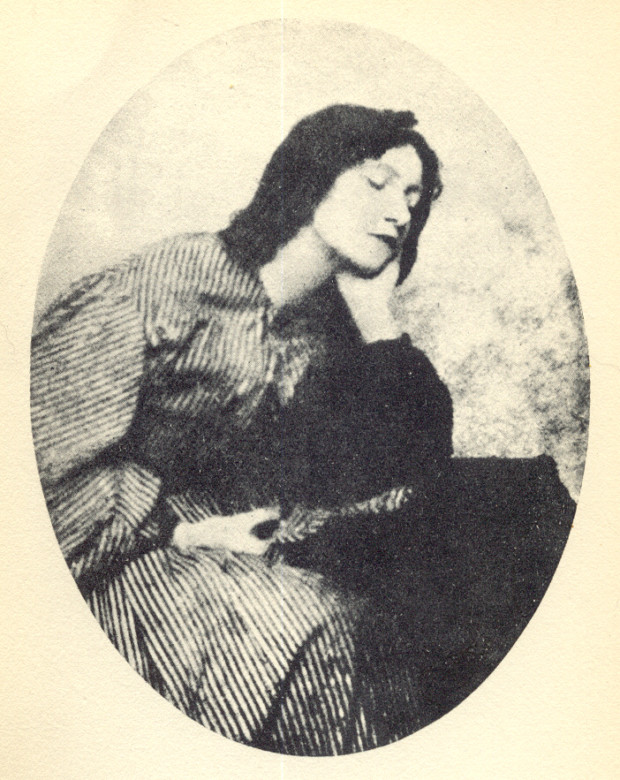

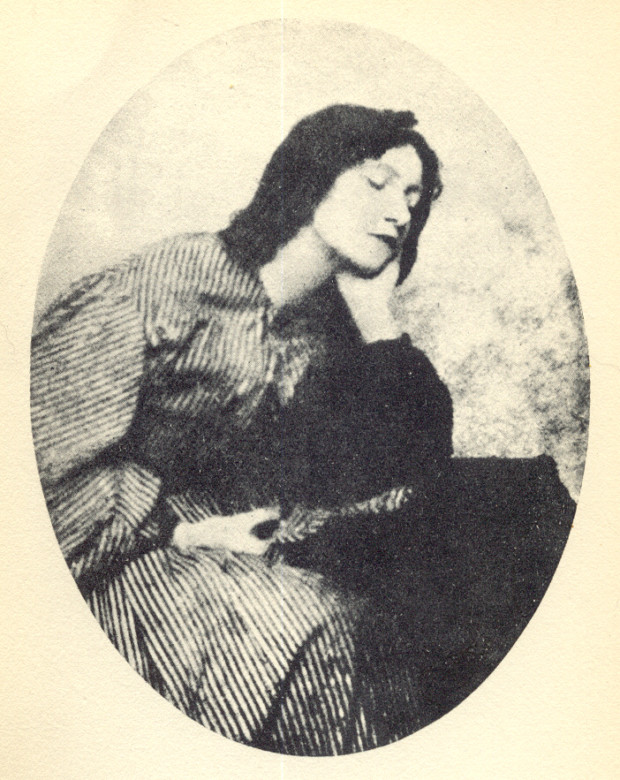

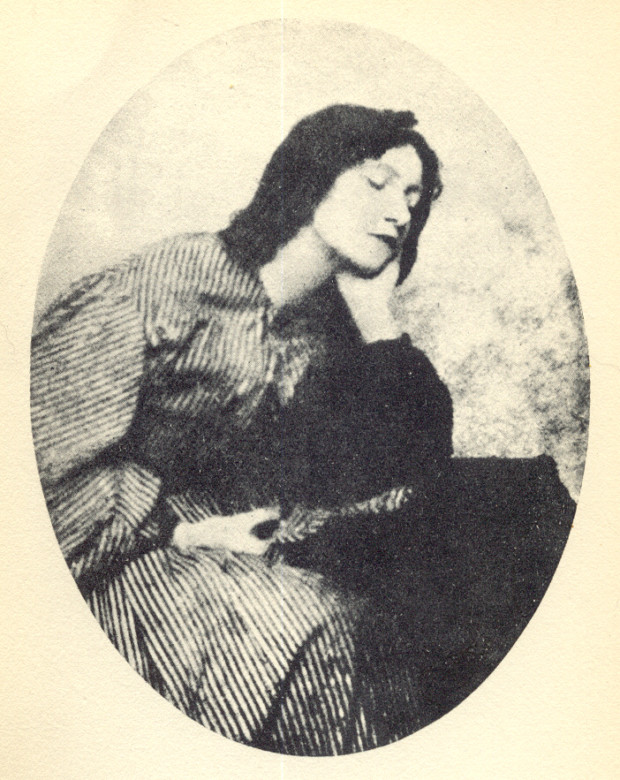

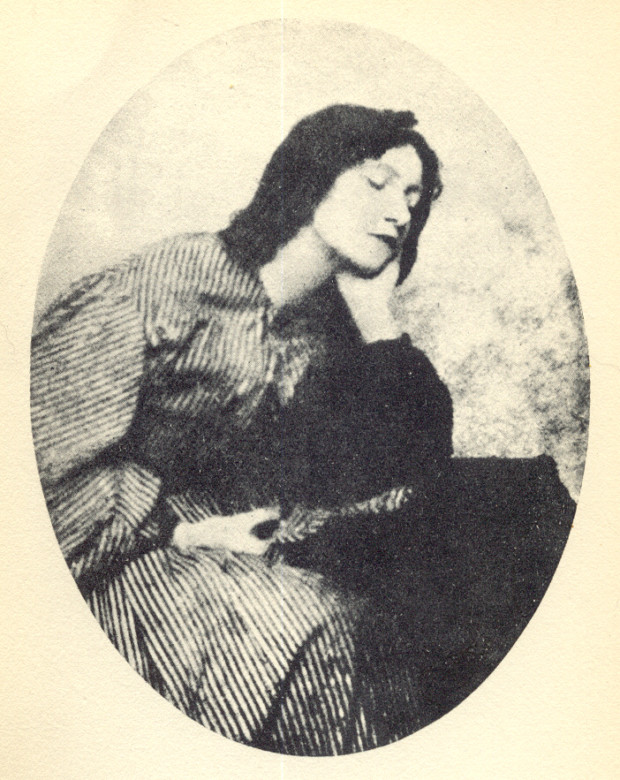

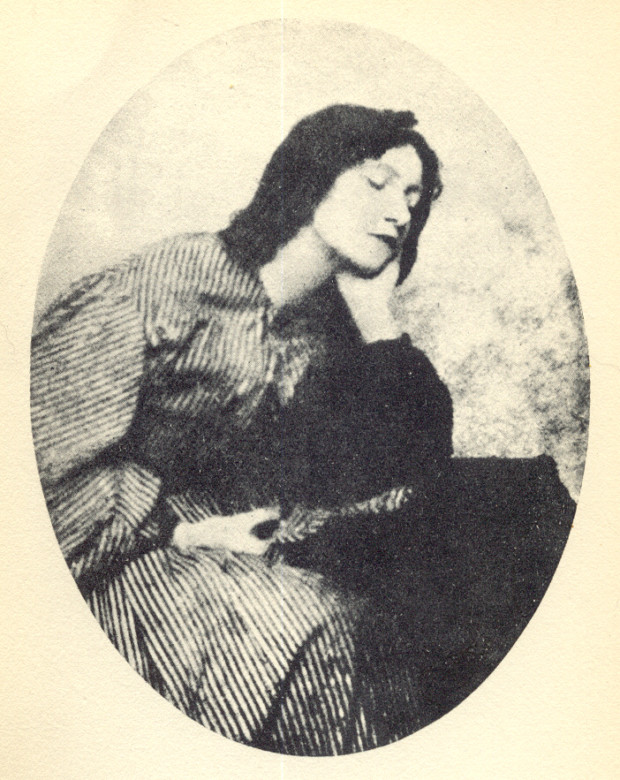

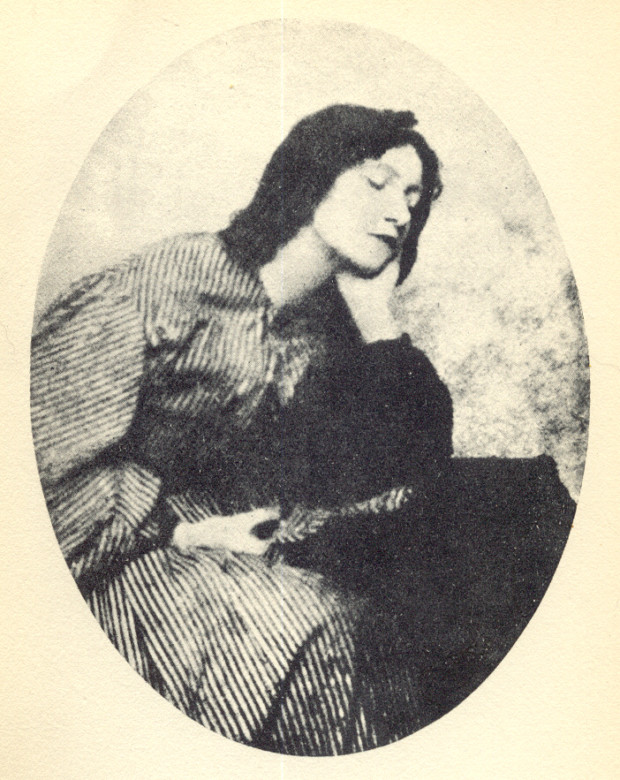

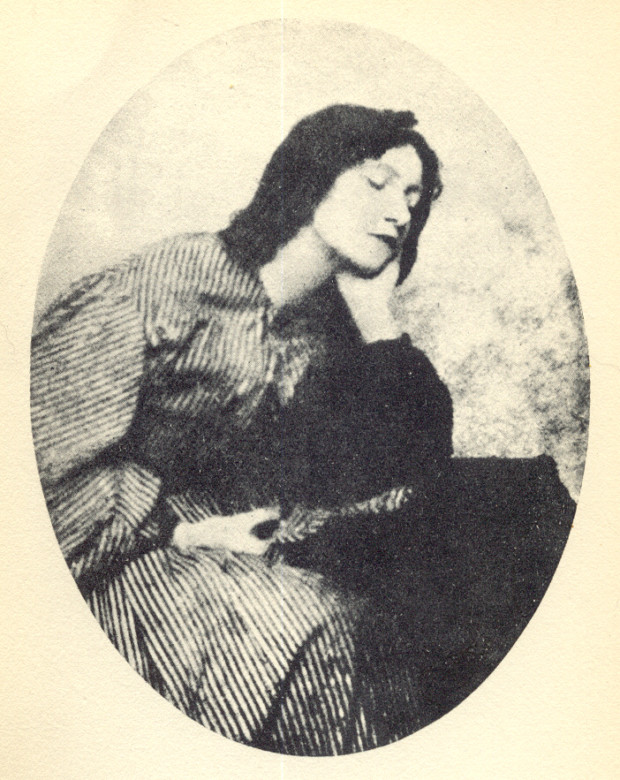

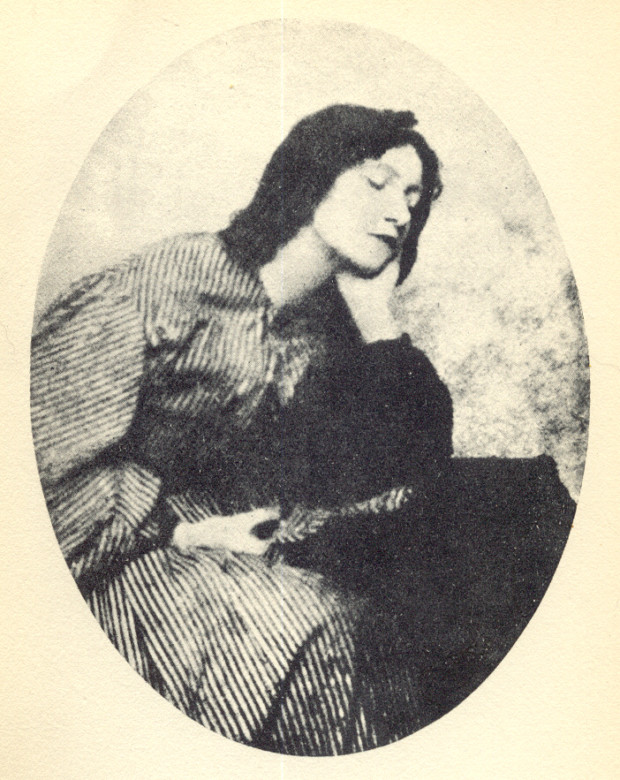

Dante Gabriel Rossetti started Beata Beatrix in 1863 after the death of his wife Elizabeth Siddal (1829-1862). The painting illustrates the last chapter of the poem La Vita Nuova by Dante Alighieri, the Medieval Florentine writer. The female figure is Alighieri’s beloved muse, Beatrice Portinari (1266-1290), and was the inspiration for Siddal’s portrait. Through symbolism, Rossetti ties two love stories together: one of Beatrice and Dante and the other of Siddal and himself, thus delineating their short and tragic marriage.

The Story of Dante and Beatrice

Beatrice Portinari, the Florentine socialite and a daughter of a wealthy banker, was the principal muse and greatest love of the Italian poet Dante Alighieri. Not much information about her biography has survived for our reference and most of what we know of her comes from the works of Dante himself. According to the writer, their relationship was an embodiment of ideal love. In Medieval terms, it was a courtly love, which is often secret, unrequited, and considered a highly respectful form of admiration for somebody.

However, by modern-day standards, the relationship was technically non-existent. It was said that he met her only twice in his entire life. The first time was when Dante was just nine-year-old, but it didn’t stop him from falling in love with her. The second and final time, was eight years later when they barely exchanged modest salutations in the Florentine street. But Dante carried the elusive image of Beatrice throughout the years and was inspired to create his most important works.

His autobiographical text, La Vita Nuova, is filled with love letters to her and, subsequently, concludes with a verse mourning her death. In Divine Comedy, she appears as a heavenly spirit who caused and guided him on his trip through the afterlife. Dante refers to her as “my savior”, because the courteous and noble feelings he has for her guide him towards what’s divine and perfect. That is why he also calls her the “glorious lady of my mind”, for the idea of a perfect Beatrice exists only inside the writer’s head. In real life, Beatrice married a banker in 1287, meanwhile, Dante had a family of his own too. Three years later she died at the age of 24.

Siddal and Rossetti

The story of Rossetti and Elizabeth is one of romance, obsession, and tragedy. Rossetti always identified Siddal with Beatrice from the very beginning of their relationship. This identification, however, took a chilling turn when Siddal died in February 1862, repeating the fate of Beatrice herself.

Symbolism in Beata Beatrix

The dove, the standard symbol of love, appears as a messenger of death, bearing in its beak a white poppy, which stands for sleep or death, and perhaps is also a reference to opium. (Siddal died as the result of a laudanum overdose.) Right above the dove is a sundial pointing at number nine symbolizing Beatrice’s death in La Vita Nuova, which occurred at nine o’clock on June 9th, 1290. The moody light and hazy atmosphere create a halo-like aura, together with the beatific expression on her face, suggests her “sudden spiritual transfiguration”, as quoted by Rossetti.

Behind the figure, a dim silhouette of a bridge disappears in a glowing light. This has often been identified as the Ponte Vecchio of Dante’s Florence. But it is vague enough to be doubled as Blackfriars Bridge in London, which Siddal and Rossetti lived next to during their marriage. Finally, the two figures in the background, of Dante on the right and of Love, symbolized by the color red and holding a flame, on the left.

Some say Rossetti’s painting celebrates love in its most beatific form, like Dante, because, alas, it was something Rossetti exercised better in art, rather than in real life.