Steven Evans knows how a moment on the dancefloor can echo down the years. Over the past three decades, this Houston-based multimedia artist, writer and curator has explored the connections between music, language, memory, identity, and collectivity via his sculptural and installation work.

Evans serves as Executive Director of the award-winning arts organization FotoFest International, and has held a number of senior positions within the arts, including Managing Director of Dia:Beacon and Director of the Linda Pace Foundation in San Antonio, while simultaneously maintaining his own career, showing his work in numerous cities across the globe.

Through September 6, the New York City AIDS Memorial hosts Evans’ s sculptural installation Steven Evans: Songs for a Memorial as part of its ongoing series of visual art and cultural programs that illuminate the history and future of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in New York City.

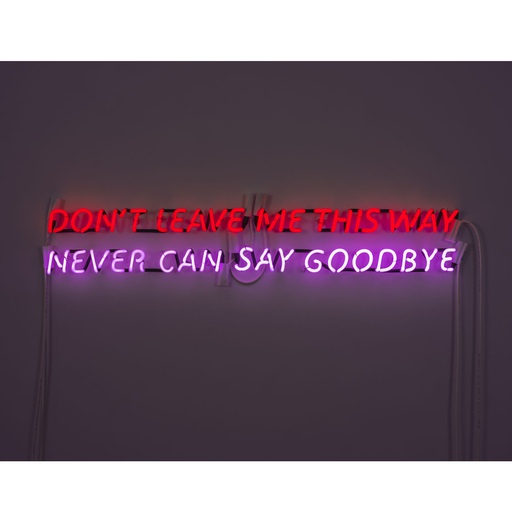

To mark the occasion, Evans has created Don’t Leave Me This Way/Never Can Say Goodbye, 2022, an accompanying, neon sculpture in an edition of 10, which combines the titles of two disco anthems tied inextricably to the period surrounding the onset and height of the AIDS epidemic: “Don’t Leave Me This Way,” (recorded by Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes in 1975, Thelma Houston in 1976, and The Communards in 1986) and “Never Can Say Goodbye” (recorded by The Jackson 5 in 1971, Gloria Gaynor in 1974 and, again, by The Communards in 1987).

Proceeds from the sale of the edition will support the New York City AIDS Memorial, which was dedicated in 2016 to honor the more than 100,000 New Yorkers who have died of AIDS and to acknowledge the contributions of caregivers and activists who mobilized to provide care for the ill, fight discrimination, lobby for medical research, alter the drug approval process, ultimately changing the trajectory of the disease.

In this interview, Evans describes his thinking behind the edition, his work at the Memorial, as well as his memories of those times, and how he feels his work now reflects the present day.

Left to right: New York City Council member Erik Bottcher, David Klonkowski, artist Steven Evans, NYC AIDS Memorial Executive Director Dave Harper

You studied photography as an undergraduate and then widened your artistic practice – what attracted you to photography originally? I like photography’s capacity to tell stories and have people connect emotionally with the subject. I like its ability to ‘play with the truth’. For me, the purpose of becoming an artist was to communicate, and photography is a particularly apt medium to do that. But then I also wanted to move beyond so called straight photography. I started doing that in my last year in undergrad and moved towards an installation type practice.

This began with using different panels of color to reference art movements and certain gay content into constructivism and de stijl-type compositions and also to position photography powerfully within the space.

One of the works I did early on that ended up getting shown in New York was called Dark Quadrilateral. I took a famous documentary photo of gay concentration camp internees and put it into the quad shape that Malevich used. Then it was hung up high in the middle of the room so that the three or four men with the triangles on their uniforms were gazing down on the whole room, witnessing the present.

Steven Evans: Songs For A Memorial

When did the text element emerge? Again at graduate school by using sculptural found objects – including a motorcycle – and weaving in text and neon and photography. That MFA graduation thesis show was the first time I used song titles and they were painted on the wall in a list that was then also made into a soundtrack. It’s the only time I’ve used a soundtrack that plays in the gallery space. I learned from that MFA thesis show that not having the soundtrack actually opens the piece up to interpretation.

What sort of reaction did the work get? One of the difficult questions I got from my committees was ‘how is this art and not a political occupation of the gallery? And I said, ‘it is both’. And that was the impulse at the time. Originally the work was geared towards putting gay content in a contemporary art practice. But later in understanding the individual and collective content of the work or associations that the work opens up I understood that the work was for everybody.

The real purpose of using the song titles is to evoke a memory and to compare individual and collective memory and history and association. We might all know that The Communards covered Don’t Leave Me This Way, but we might also have an association with a lover or someone that that song triggers – so it’s specific to everyone. I think at times it’s about you and the person you’re dancing with and everybody else disappears.

Don’t Leave Me This Way/Never Can Say Goodbye, 2022

You were friends for a time with Felix Gonzalez-Torres who said he created his works for his partner, Ross (Laycock). Who do you have in mind? I think a lot about when Felix said that, and I think my work is also about relationships in many cases. That’s where it triggers whether it’s romantic or not. I did a work called If I Can’t Dance It’s Not My Revolution and it tracked song titles every year since Stonewall. One of the songs was You Are My Sister, and that was incredibly popular with millennials. Everyone ran to take selfies with that title because it connected them to their family – biological or chosen.

In a way, songs or song titles are a little like ready-mades, did you ever see them like this?Absolutely. It’s interesting because a lot of artists say they have a research-based practice, and I’m not sure that every artist means the same thing when they say that. I feel like my practice is more of a hybrid, but it is also based on researching history.

When I started this work the internet as such didn’t exist. I spent a summer at Lincoln Center researching the microfiche of their Billboard magazines and writing down the songs that represented the mission of what I was trying to accomplish with this work. So, in that sense, they were ready mades in that they were waiting there in the historical record ready to be accessed and be referenced and used.

What was your criteria when you were searching? The song title or the actual lyric? A mix. I would say I think that I like songs generally that have a narrative to them so that people insert themselves into the narrative or they think about how the lyrics of the song relate to their lives and I am drawn to declarative songs that really talk to my audience as well as the audience for the original song.

Steven Evans: Songs For A Memorial

A song like It’s Raining Men being illustrative of that. . . I felt that at the time. I remember thinking at the time that this song really has a double edge. . . There are also some formative experiences. I went to boarding school for a time and they would do dances. I was 16 or 17 and the DJ was playing I feel Love by Donna Summer and people were dancing and enjoying it. And the DJ took the needle and scraped it across the record and had it stop and immediately went into My Sharona by The Knack. So it was kind of a disco sucks statement. I’ve always remembered that as how and why I came to be making this work.

I don’t know if I’ll ever totally understand but that experience was important. I really identified as a teen with disco and remember going to my first gay bar when I was 17. I still remember many of the songs I heard that night. It was a club in Charleston, South Carolina called Les Jardins, and it was all new to me and very exciting. I remember it was the first time I heard Planet Rock and Glad to Know You by Chas Jankel and a bunch of other songs.

Disco is having a big moment in London clubs at the moment! I think it’s having a moment here again too! There was an article in the New York Times about this couple who bought a house in Fire Island Pines and found a treasure trove of cassettes from the club there. And it’s become a popular article on the New York Times site. So maybe there’s something in the air. It’s ripe for reassessment.

How did you work all this into the memorial piece? What were the challenges? Well as the site is a memorial, I mostly used historical songs, but also songs that had been covered by more than one person or a song that shares a title with a number of different songs.

Why, by Bronksi Beat, is also a song by the Jacksons and by Annie Lennox. But I was really thinking about how songs lasted from the 70s through the mid 90s – the worst years of the crisis. There are a lot of people my age and older spending time at the Memorial, and I imagined them thinking about friends, lovers and family that they have lost. So while the piece is for everybody, it’s really for those people.

What I wanted to do was really insert some tools for people to connect with their loss but also the good times they had with people and to remember dancing, to remember maybe having good times before they knew about AIDS and also when they knew what they were facing.

Every song I’ve chosen is important to me for the ‘notes’ I want the Memorial piece to hit. Don’t Leave Me This Way and Never Can Say Goodbye were the first two songs on the list. Others were I Will Survive, Don’t Make Me Over (the Sybil cover of the Dionne Warwick song), Got To Be Real, Why, Do You Wanna Funk, Love Is The Message, Tears, and All Around The World.

Don’t Make Me Over was important to me. I remember the early years of the crisis and activism, and people working with AIDS working to take control of the image and the narrative. The word ‘victim’ was thrown around a lot and we didn’t like that. So Don’t Make Me Over really relates to that time.

I love the way certain songs can talk to each other and make a third meaning. I’m a big fan of Don’t Leave Me This Way and Never Can Say Goodbye, for that reason. I realised how they were working together in the Memorial and that’s why I brought them together into the Don’t Leave Me This Way/Never Can Say Goodbye, 2022 multiple.

Both of those songs existed as Seventies disco songs and then they were covered by The Communards, and I think I know that Jimmy (Somerville) has really connected with that history and this is almost my way of covering those songs. And also, some of the earliest works I made were two songs coupled together and this is the first time I’ve done that in neon. Previously they were paint and vinyl.

Don’t Leave Me This Way/Never Can Say Goodbye, 2022

There’s something universally attractive about neon isn’t there? The glow that comes from within it is really important. Going back to my beginnings I was looking at conceptual artists like Bruce Nauman, Joseph Kosuth, Lawrence Weiner, and ways to use language – if you’re going to make something about identity as opposed to philosophy. So that was what attracted me to neon.

The thing I like about making the song titles in neon is the idea of the owner or the holder of the piece turning all the other lights out and having this song title glowing in the dark as if they were in a club. Of course, they also function in light.

That’s an important part of using neon for me. I like it as a certain kind of descriptive system. Disco goes with neon for me. Even tacky TV programmes like Deney Terrio’s Dance Fever. Aesthetically it’s a very sensible easy connection with disco music. And it’ll look great in the home!

What were the challenges in getting the multiple just right? There was work with the neon fabricators to make the kerning on the letters really specific to make them justified right and left so that they are really are like a block.

I don’t use handwriting like Tracey Emin – whose work I admire very much – and I like the way she subverts neon. But I take a less immediately visible approach where you think it might be say, a Joseph Kosuth phrase, and then you realise it’s a disco song, I like that.

And the subtle change in the letters from the deep red to the fuchsia is also really important. I wanted that hotness to those colors, and I think they vibrate with one another – which I like a lot

Finally, what are you listening to these days? I don’t go out as to clubs as I used to but I’m into Hot Chip and also Ant.Honey, Troye Sivan, and Perfume Genius. Perfume Genius is a genius! Hercules and Love Affair and Róisín Murphy and SSION. I’m obsessed with At Least The Sky Is Blue.

I’ve done song lyrics by Iggy Pop and The Smiths, and Tears For Fears and there’s all different kinds of bands that are referenced. My practice has really opened up now. In the beginning, it was questioning what is gay identity? And how did this music play into it? And that was a journey for myself and a journey for the gay community as we were forming identities.

Find out more about the good people and work of the New York City AIDS Memorial here and read more and maybe purchase Don’t Leave Me This Way/Never Can Say Goodbye, 2022 here.