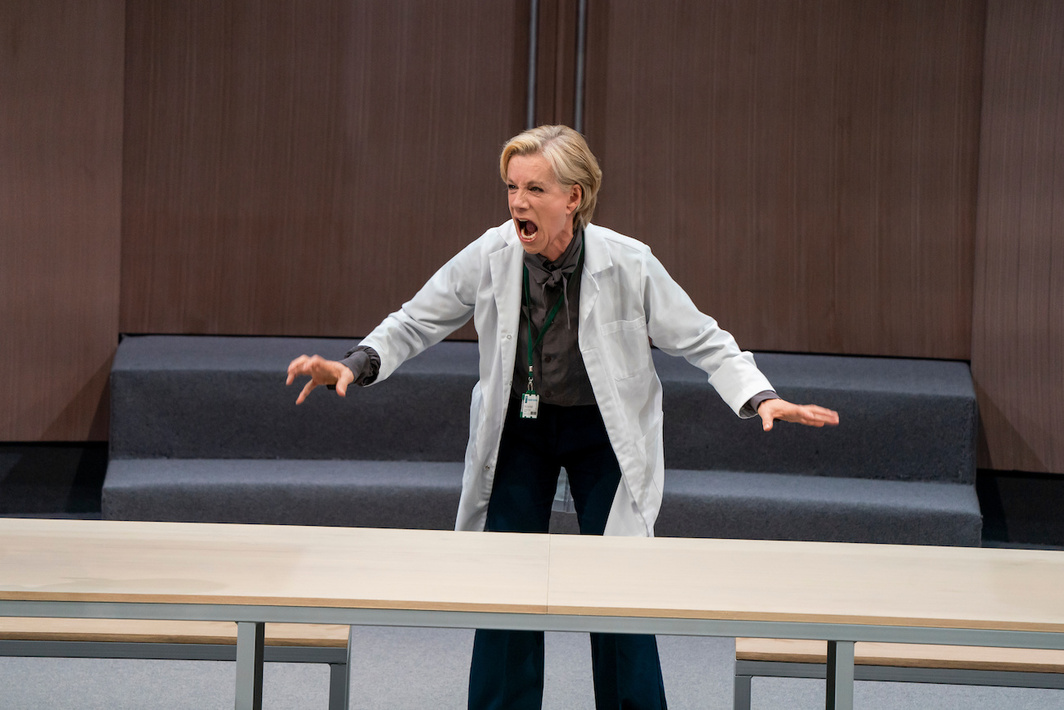

Robert Icke, The Doctor, 2023. Performance view, Park Avenue Armory, New York. Ruth Wolff (Juliet Stevenson). All photos: Stephanie Berger.

“FOR A DOCTOR, language is precise—a diagnosis has to be specific,” remarks Ruth Wolff, a secular Jewish physician in Robert Icke’s The Doctor. Played with refractory aplomb by Juliet Stevenson, she palpates words for hidden biases, chafes at the use of churched-up terms like “development” in place of the more honest “asking people for money,” and gets in a high dudgeon any time someone confuses “who” for “whom” and “literally” for “figuratively” (and vice versa). An oddity, then, that her name fuses the all-too-apt “wolf” with the benignant “ruth.” The onomastic irony is lost on Wolff’s colleagues, most of whom refer to her by her last name only, or as “the BB” (short for Big Bad). Only with her partner (Juliet Garricks) and a trans teenager (Matilda Tucker) whom Wolff takes under her wing does Wolff allow herself to be remotely vulnerable, to be human.

Following acclaimed runs at London’s Almeida Theatre and the West End’s Ambassador Theatre Group Productions, this stem-winder of a “moral thriller,” “very freely adapted” from Professor Bernhardi by the modernist Austrian dramatist Arthur Schnitzler, opened at the Park Avenue Armory in New York earlier this month. Icke’s version, set in the present day, builds on the bones of Schnitzler’s somewhat obscure 1912 play, which dramatized the fall of a Jewish doctor who stood for tenets of universal humanism against Catholic dogma, and adds a seminar’s worth of material. Along with a conflict between science and faith, the play stages the vicissitudes of navigating identity as a trans teen, the mob mentality of “cancel culture,” the erosion of principles by currents of political expediency, the misogyny and racism of modern medicine, and the difficulty of separating one’s professional and personal lives.

The Doctor pivots on the death of Emily, a fourteen-year-old girl who enters sepsis after a self-administered abortion. Wolff, the founder of an Alzheimer’s institute, takes Emily in and attempts to treat her, to no avail. Minutes before she passes, a Catholic priest (John McKay) materializes at the hospital, seemingly at the behest of Emily’s absentee parents, to administer last rites. Wolff adamantly refuses on the principle that Emily has not explicitly asked for sacraments and that to snap her out of her sedated state would cause “an unpeaceful death.” “You walk in there like the grim reaper and there is no way that she, in her current condition, can die without panic and distress,” she tells him. In the aftermath of Emily’s death (which happens offstage), news quickly spreads about Wolff’s dismissal of the priest. Soon, a petition is making the rounds online advocating “that Christian patients need Christian doctors.” Signatures gradually tick up from dozens to just under one hundred to over fifty thousand; Wolff finds herself the proverbial frog being slowly boiled alive. (As a study of an austere, professionally accomplished queer woman who is toppled from a position of power, the play puts one in mind of the film Tár.)

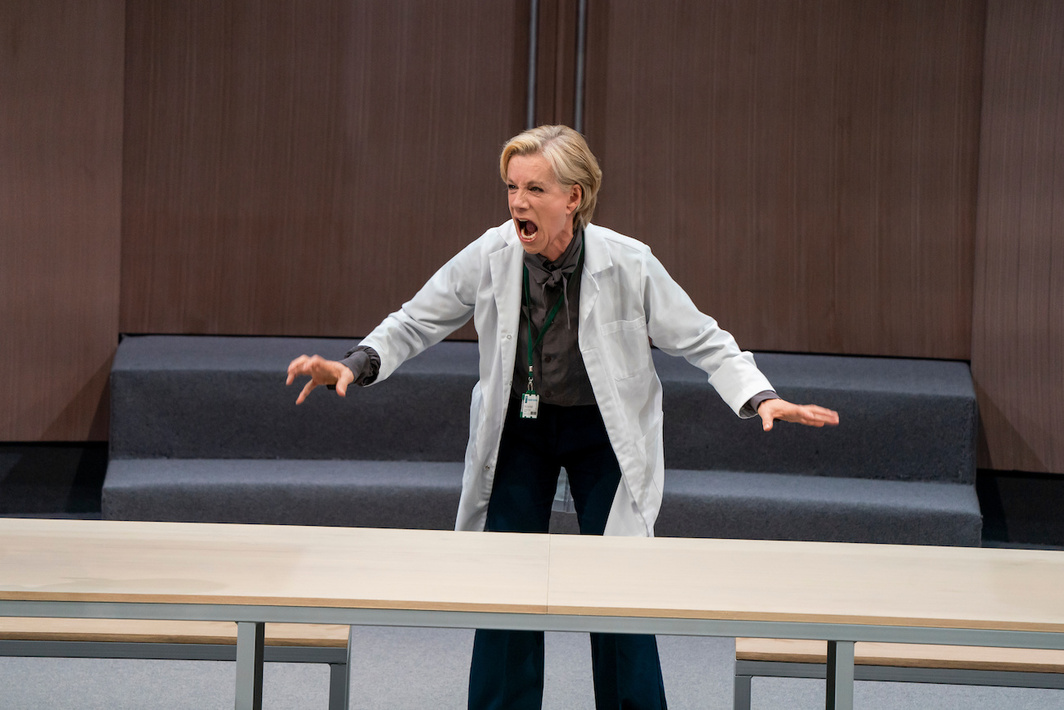

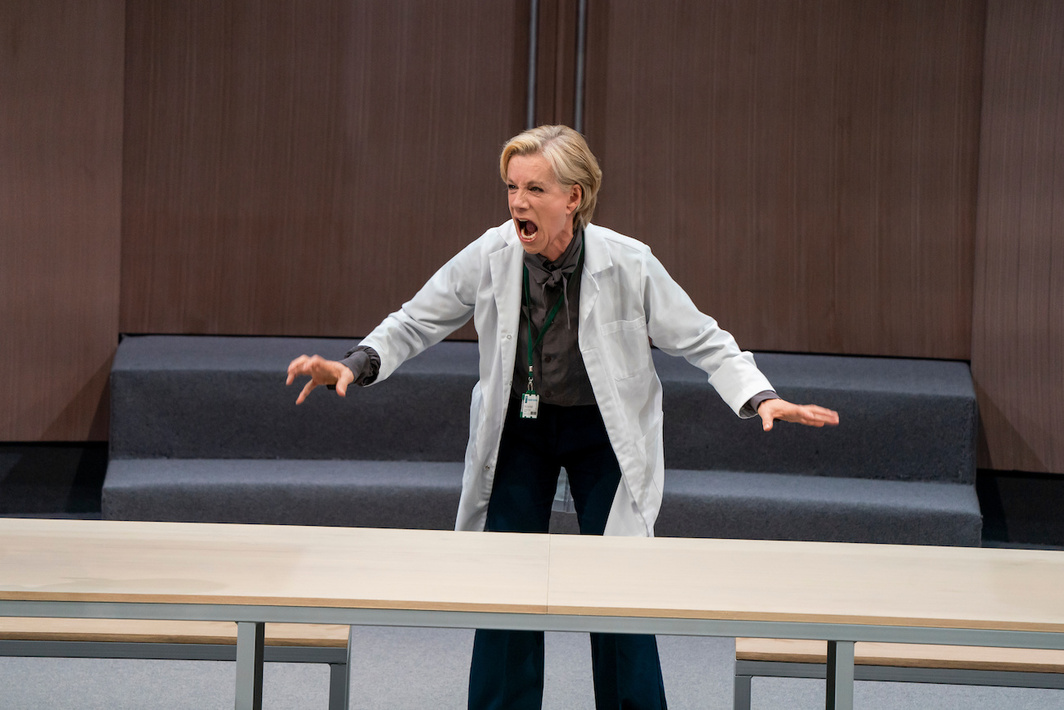

Robert Icke, The Doctor, 2023. Performance view, Park Avenue Armory, New York.

On Hildegard Bechtler’s curved, wood-paneled set—bare except for a long table, a couch, and some benches—a group of Wolff’s peers and a press officer assemble in the hospital’s inner sanctum to deliberate. Should Wolff publicly apologize and nip the PR crisis in the bud? Circulate a statement to the hospital’s board to try to preempt a vocal contingent of antiabortion activists? Invite an external inquiry to demonstrate transparency? All these extra-medical concerns are anathema to Wolff’s conception of her role as a doctor—she thinks it demeaning to perform her humanity for a jury of her inferiors—but other members of the executive committee think the issues deserve a full airing. For some time, there has been more than the usual intramural squabbling over the appointment of a new department head, and the overworked committee has factionalized. (The turntable set adds perhaps unintended resonance to the phrase “going in circles.”) It comes as little surprise when Hardiman (a steely Naomi Wirthner), Ruth’s foremost opponent at the institute, proposes a motion of no confidence in its founder. Despite this blow, Wolff manages to remain her dispassionate, even-keeled self. When she later discovers that someone has defaced her car, she muses: “Do you think the swastika is a reference to my Jewish roots, or does it more generally denote my alleged fascism?”

In Schnitzler’s play, the death of the young girl culminates in a court case, after which the male doctor is imprisoned for two months and barred from practicing medicine. Icke shuffles along for a time in Schnitzler’s footprints before throwing off his leading strings; his modernized version reaches a climax when Wolff gets hauled before a debate talk show during which five ax-grinding guests, including an academic specializing in postcolonialism and a historian of Jewish culture, fire questions at her, chipping away at her veneer of neutrality. Drummer Hannah Ledwidge, suspended directly above the stage, punctuates cliff-edge moments with a propulsive beat (Tom Gibbons provided the sound design and composition) while close-up projections of Stevenson’s face during the inquisition reveal every twinge of doubt, every nostril flare of indignation.

The televised debate also marks an inflection point in the play. Up until this point, almost all the actors (except Stevenson) have played characters with different genders and ethnicities from their own. As Icke elaborates in the script, the move is intended to make the audience “reconsider characters once an aspect of their identity is revealed by the play.” The maneuver comes across as superfluous at best and obfuscatory at worst. The contingency of identity is, after all, already crystallized by Ruth when she asks: “Thought experiment: If I were a man, do you think you’d be dealing with this differently?” Later, a panelist on the debate show turns the question back to her: “Had the priest been white, would you have acted the same way?” The priest, played by a white man, is gradually revealed to be Black, while Hardiman, referred to as “he,” is played by a woman. It’s unclear to what end these matrices of identity are being altered. What, exactly, are we being asked to “reconsider”?

Robert Icke, The Doctor, 2023. Performance view, Park Avenue Armory, New York. Charlie and Ruth Wolff (Juliet Garricks and Juliet Stevenson).

One needn’t be a Freudian to believe that the human psyche has both masculine and feminine components, and to therefore think that the play is, in part, about the repression of what physicians used to called “psychic hermaphroditism.” But the issue of race tugs the play in a different direction and shows the limits of Icke’s lava-lamp ontology. Sometimes, the racial gaslighting seems nothing more than a Socratic exercise. Other times, casting across race seems to make a point about the privileges that come with passing, as when one of Wolff’s colleagues (played by a white actor) protests “I’m a Black man! My grandmother was born in Kenya,” only to be told by another doctor that “it’s a slightly different story when you look completely white.” It is telling, though, that when the televised debate reaches full flood, it is a researcher played by a Black actor who takes Wolff to task for using racist language like “uppity” and for thinking that words can be value-neutral. As she says, “It astonishes me that you dismiss the whole idea of labels or titles or name,” and, twisting the knife further, “Language is step one—because some of us have to push back before we get to choose, select how we are described.” On the page, the ideas may seem innocent of originality, but what rescues the scene from sinking into a satire of every implicit bias/racial justice training workshop is the banal fact of her identity: A Black woman speaking these words corrects the play’s astigmatism with regard to identity and makes things “crystal clear,” as Wolff would put it. But only for a moment; the final moments of the play see another encounter between Wolff and the priest, and, without giving too much away about the play, we might wonder at the end if we’ve been deposited right where we started.

One is tempted to say that Icke could have gone further in taking risks. What might the play have looked like had the roles chosen the actors each night? Would lines accrue greater meaning when spoken by a spectrum of different performers? Would our understanding of the characters change? It’s an impossible question, of course, even leaving to one side whether audience members would be willing to sit through multiple three-hour performances to see actors play different characters. Theater, like therapy, has its uses for forms terminable and interminable. But the one visit may be enough.

The Doctor runs at the Park Avenue Armory in New York through August 19.

ALL IMAGES