A Man of Many Names

One possible reason for our ignorance could be his name – he had several versions: Jacopo Carucci, Jacopo da Pontormo, Jacopo Pontormo, or simply Pontormo. Try editing that lot into an art history textbook!

Vasari vs Pontormo

Another reason why we may not know of him is laid at the door of Giorgio Vasari, the first art historian. Vasari was best known for his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, published in 1550. This mammoth tome is considered the ideological foundation of all Western art history writing. Vasari even popularized the term “Renaissance.”

Rivalry

Vasari’s own art workshop was in direct competition with Pontormo – did he snub Pontormo out of jealousy? Vasari did, however, include Pontormo in the third section of his Lives of the Artists alongside Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Titian.

Vasari describes Pontormo as being a neurotic loner, terrified of death, and even a miser, but he is mentioning Pontormo as a person and not as an artist. Of his works, Vasari is fulsome in his praise. He admired Pontormo technically and commended his experimentation and innovation. Hmm, complicated.

Genius Contemporaries

It is clear that competition from other artists was a factor in Pontormo’s lower profile. The artist’s life and his desire to move in a different direction stylistically coincided with outpourings from three giants of the Renaissance: Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael. In a period containing the extraordinary talent and polymathic skills of those three geniuses, is it any surprise Pontormo was overlooked? A final, very practical explanation for poor Pontormo’s lack of popularity is that much of his work has been lost or damaged. But thankfully, enough remains for us to appreciate. So read on!

Superb Draughtsman

Here is the man himself. This dynamic image illustrates what a superb technician and draughtsman Pontormo was. The chalked image is arrestingly modern, although it is almost 500 years old.

The Deposition

Another self portrait can be seen in The Deposition, a work that is a flurry of emotion and movement. Pontormo paints himself into the upper far right of the canvas, probably as Joseph of Arimathea. He stares out at us, almost as if he is giving us, the viewer, a passing glance before he walks out of the image. Note how he cleverly fits his figures into the architectural niche.

Marvel over the very bright palette he uses (Vasari complimented him upon this). Another of his clever devices is his unique composition: Christ is not central to the construction, in fact, the back of a fist is the unusual center-point; the swooning Virgin is slightly larger than the rest of the figures; and all the figures, but for three, are male. However, all these men stare straight out at us: the servant in blue, John of the Cross supporting Christ’s legs, and of course Pontormo himself.

Patrons and Portraits

Pontormo, as has been observed, was a masterful draughtsman. He was also a fine portraitist and painter of religious subjects. The church commissioned many works, as did the Medicis, the famous political family dynasty who ruled Florence and Tuscany during the first half of the 15th century. However, Pontormo’s vast range of fine portraits was not just of the great and the good but of unnamed men and women. For instance, his portrait of a musician. Musicians, much like painters, were seen as servants and were even lower down the social scale than artists!

Tutors and Influences

Pontormo was initially a student of Leonardo da Vinci then of Piero di Cosimo, progressing to Andrea del Sarto. Besides these masters, other influences clearly come from Michelangelo and Albrecht Dürer. Innovations with woodcuts and the new development of printing would have reached Italy by Pontormo’s day.

Pontormo received several ecclesiastical commissions for frescos. Some of these have not survived intact, possibly through his flawed execution – after all, even the great Leonardo da Vinci didn’t master fresco technique quickly. Location was the other significant factor. Pontormo’s first set of commissions was in the cloisters of the Charterhouse monastery in Florence. Open to the elements these frescos became significantly weather damaged over time. The Ascent to Calvary (one of a series, shown above) is a prime example.

Vertumnus and Pomona

Other frescos have fared better, as in decorations in the salon of the Medici country retreat at Poggio a Caiano, in Tuscany. Pontormo represented Vertumnus (god of the seasons and growth) and Pomona (goddess of fruitful abundance) from Ovid’s Metamorphoses on a lunette, a half-moon-shaped arch (above).

This is another fine example of how Pontormo skillfully fills a fresco space. His detailing is very special, especially the masterly composition of the left-hand figures. A naked youth reaches up for a branch, whilst a clothed youth looks up at him creating an invisible diagonal. In between the naked youth’s legs stands a hound, facing us, the viewer. The depth of field and perspective are exceptional. Outside this construction of the triangle is a smaller boy (I suspect Pontormo, like many creative artists, always saw himself as an outsider) yet this small child echoes the body stance of the naked youth.

Pause further to really study the naked youth and we are almost looking at perfection: anatomically flawless, slim, long-limbed with a beautiful head tilted upwards, much in the manner of figures found in Michaelangelo’s and Raphael’s work. And note how the toes are curled in the tension caused by leaning sideways. And, I am going to mention the unmentionable: his penis! (there I have said it).

This is not a miniatured ascetic penis that so many of Pontormo’s contemporaries would apologize for. This is life-size, hanging down to the right, in opposition to the rest of the body’s movement. And there is even the suggestion of pubic hair. This is brave and even exceptional for the age since Pontormo’s contemporaries generally portrayed the male member as either so tiny that a magnifying glass is required or seen delicately masked by a wispy cloth to save our blushes.

It could be argued that Pontormo’s skill is in the detail rather than the whole. Take his Noli Me Tangere (after Michelangelo) from 1532 (above).

The work is based on a cartoon by Michelangelo from 1531, now lost, representing Christ appearing to Mary Magdalene in the garden. Yet look at the background of Christ and Magdalene and you have a delightful and perfectly executed landscape at least a century before landscape became a recognized genre. And this is not a fantasy landscape as someone such as Pieter Breughel the Elder would indulge in. This is a recognizable scene that could be found in the sun-baked lands of Southern Italy today.

Mannerism

The bold and radical was very much in keeping with the late Renaissance style Pontormo promoted. This new style, known as Mannerism, was a reaction against (or development from) the harmony, proportion, and naturalism of high Renaissance art.

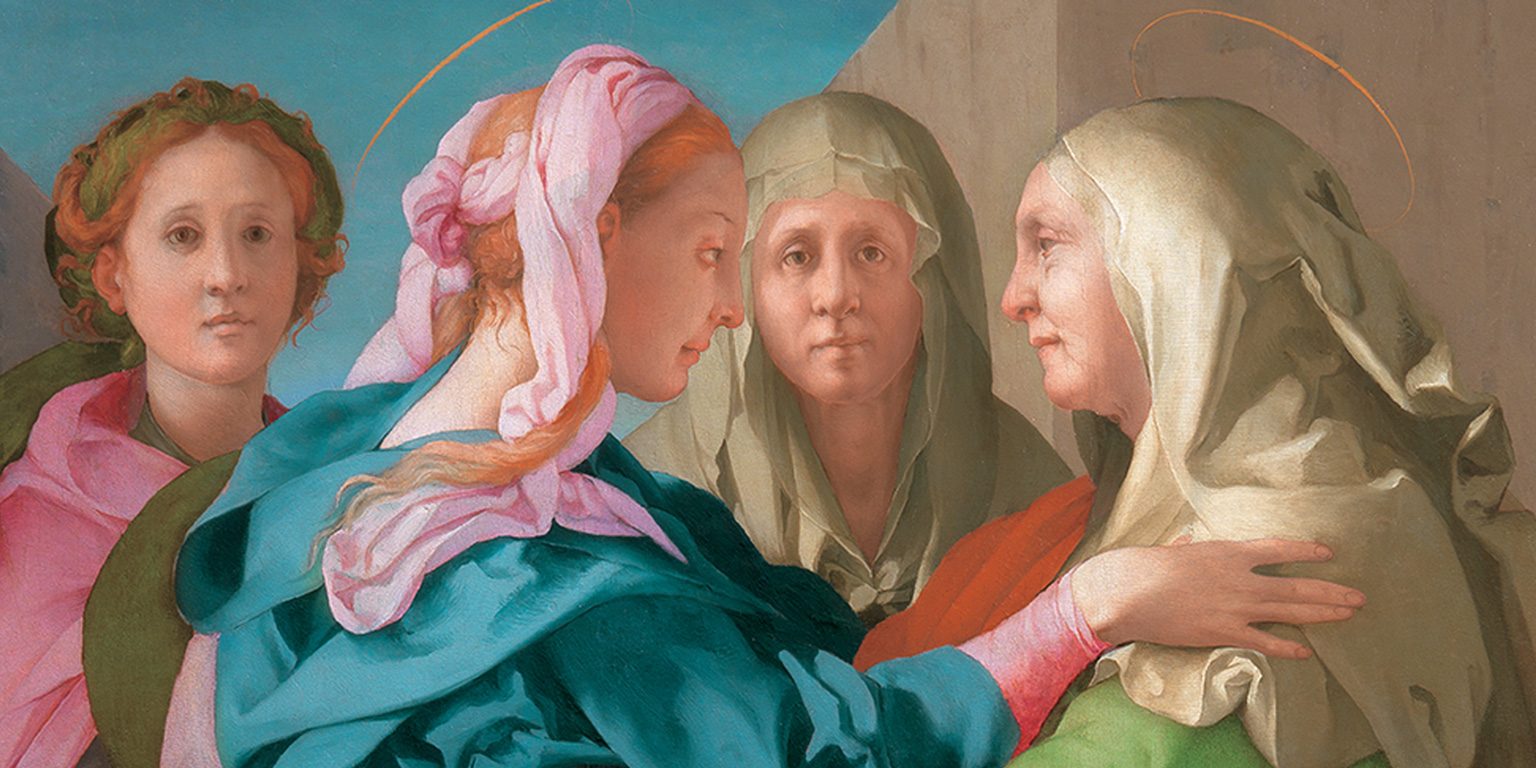

Pontormo was obsessed with style, technique, and composition. He worked with bright colors; a disconcertingly unnatural approach to space; slightly elongated or altered figures and spiraling compositions. The Visitation is a fabulous example of this, shown above. The feet barely fit the painting’s borders. Blue, pink, green, and orange fabrics billow. The puzzling perspective shows us two tiny and mysterious figures in the background. The composition of four figures in a rhombus shape echoes Albrecht Dürer’s 1497 Four Witches. A preparatory drawing still exists, illustrating that he was meticulous in his preparation.

Joseph at the National Gallery

As well as portraiture, Pontormo created some handsome and large religious and secular history works to be proud of. If you are in the UK, head to the National Gallery where you can see six works representing Scenes from the Story of Joseph.

In fact, one of Pontormo’s most popular works is from this series: Joseph with Jacob in Egypt (above). This is an episodic work, told in chapters, as was common practice in an early Renaissance painting, ending with Jacob’s deathbed (top right-hand corner). Aesthetically this seems a rather crowded and chaotic work that seems almost surreal.

Early Life and Lost Works

Pontormo was orphaned at an early age, and perhaps the loneliness of childhood made him inward-looking and reflective. It seems he was never very comfortable in his world, he was a loner, and prone to neuroses and obsessions. He kept a diary from 1554 till his death, where he cataloged his diet, illnesses, and feelings. Even his death had a socially jarring note to it as he died on New Year’s Eve 1556, aged 63. Several unfinished works were completed by other artists and a significant number have been lost forever.

The vagaries of public opinion and taste, the loss of key works, his idiosyncratic personality, sharing a stage with some of the most influential painters in the world whilst pioneering a radical shift in style – all of these have affected the position of Pontormo in the pantheon of Mannerist painters. But the few works that remain are dazzlingly luminescent, and we advise you to make a point of seeking out a perfect Pontormo.

Author’s bio

Ian Munday Since his retirement to Wales he has been studying art history and creative writing. He gives guided garden tours at Powis Castle in Welshpool and also assists at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in Machynlleth.

Here you can enjoy his article about the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo and divine buttocks!