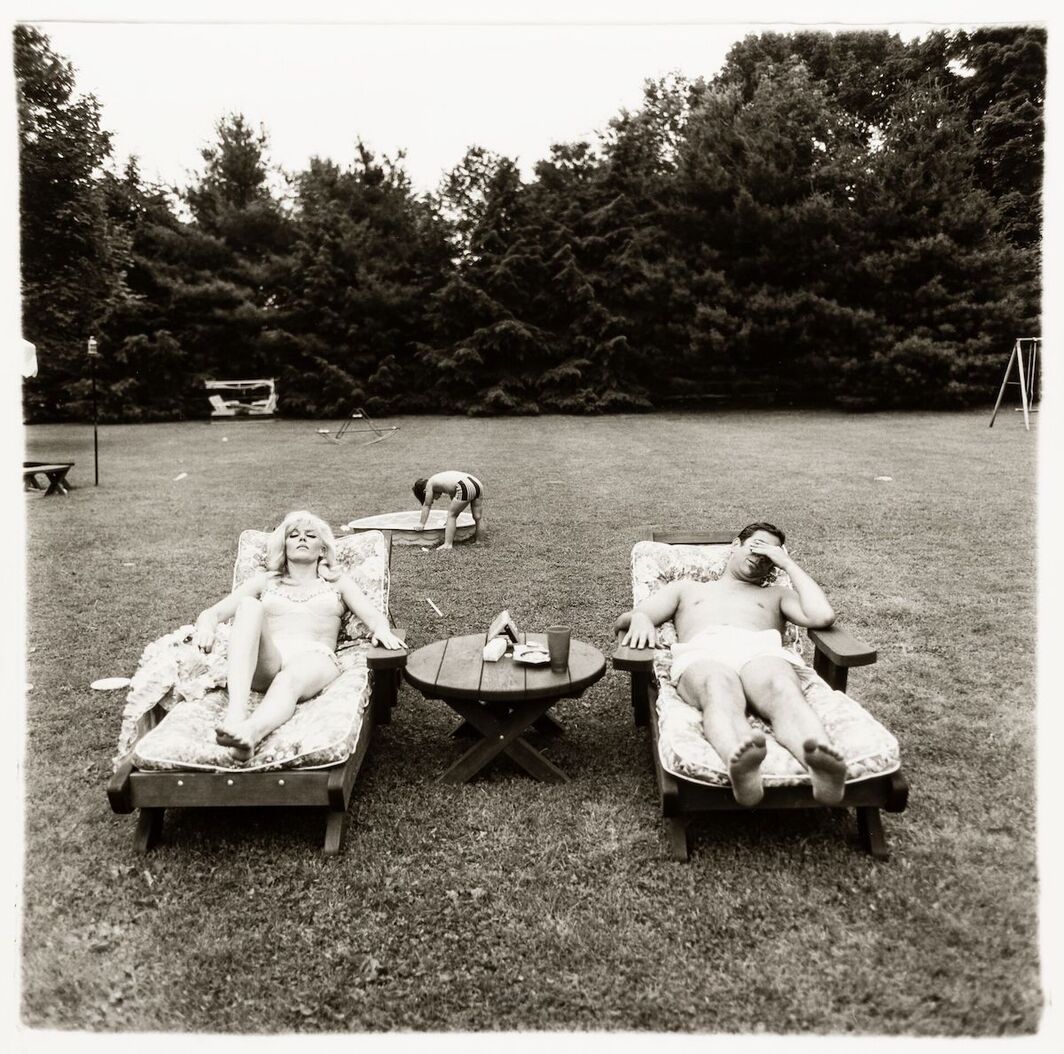

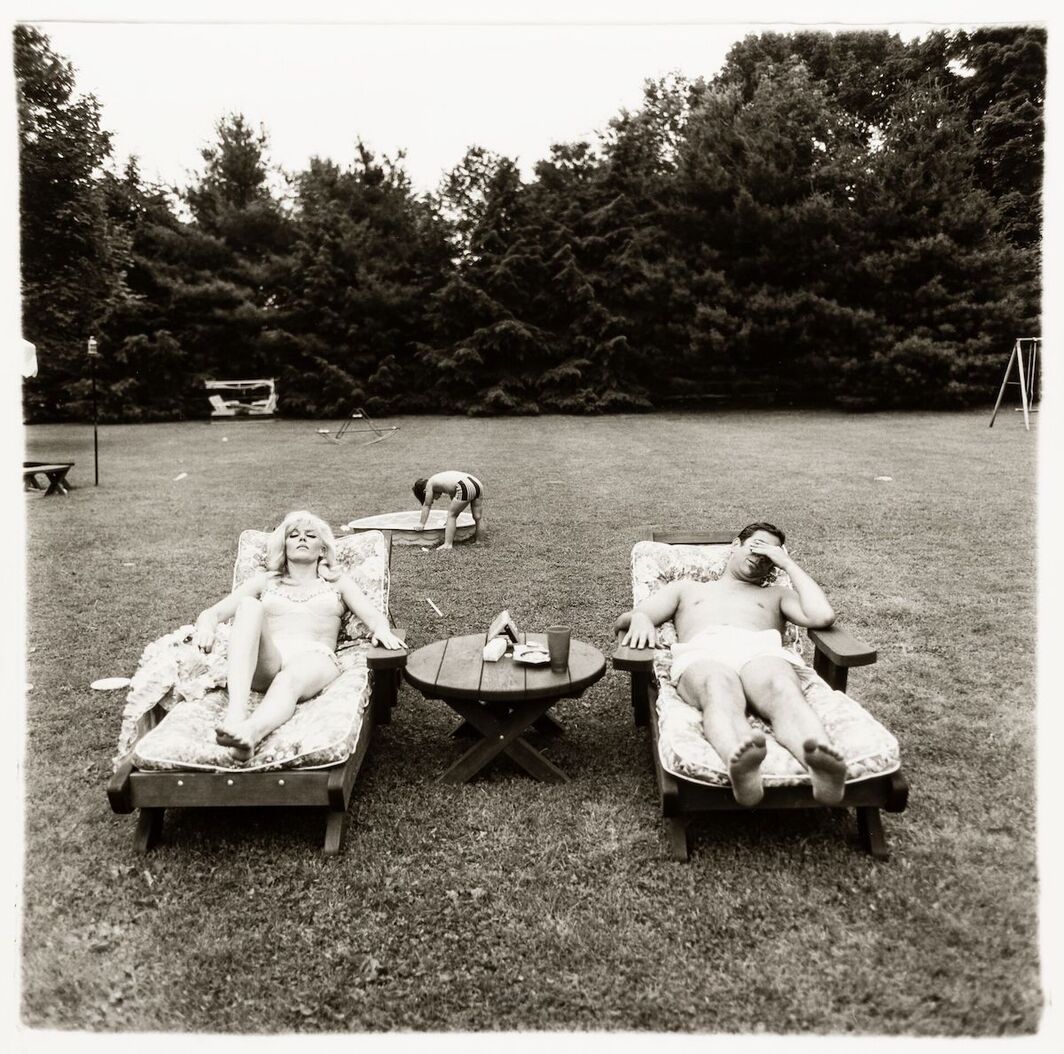

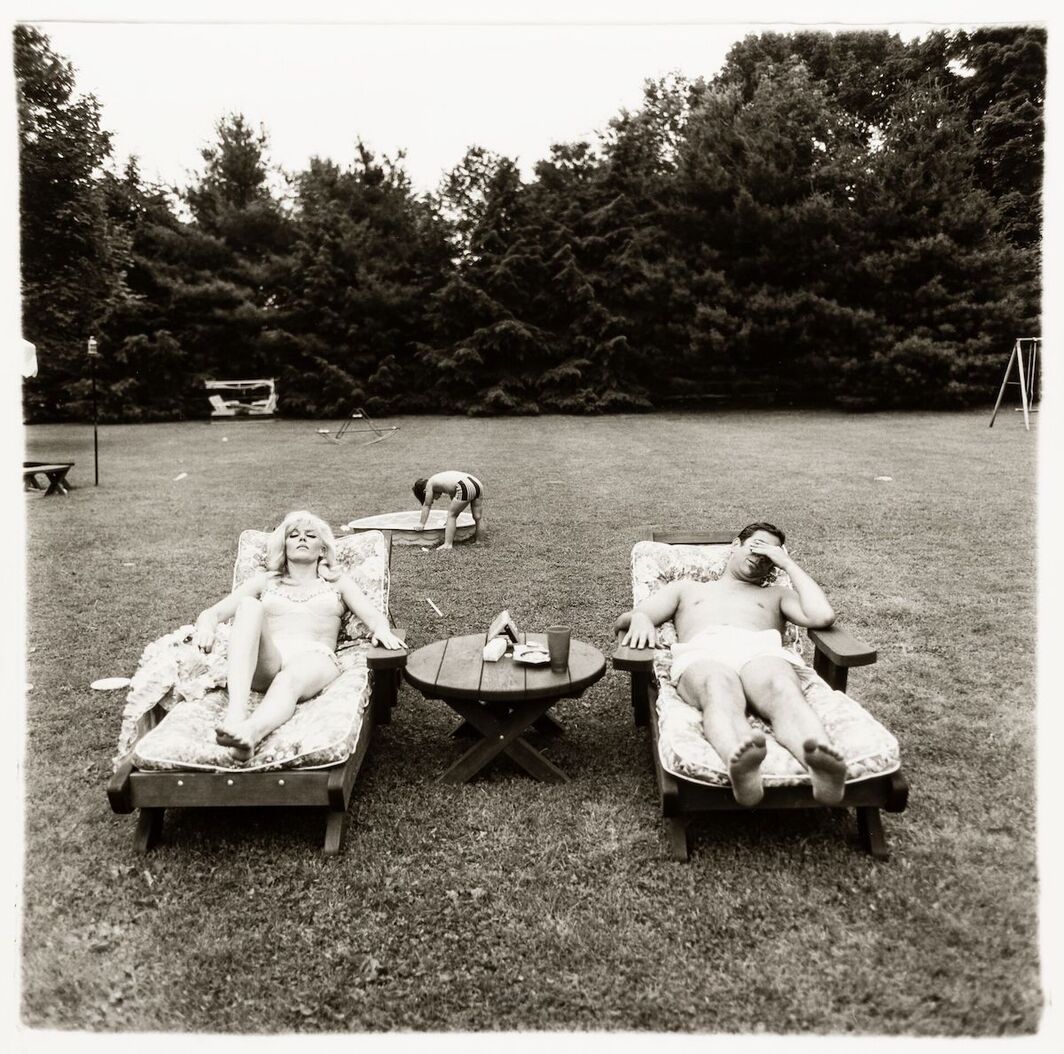

Diane Arbus, A family on their lawn one Sunday in Westchester, N.Y. 1968, 1968. © The Estate of Diane Arbus / Collection Maja Hoffmann / LUMA Foundation

Neil Selkirk is a photographer and filmmaker. In the wake of Diane Arbus’s suicide, in 1971, Selkirk was invited by the Arbus Estate to make new prints for her posthumous retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art—a landmark exhibition widely credited with elevating photography’s popularity and fine-art status. Selkirk became the only person authorized to print from Arbus’s negatives and continued collaborating with the estate until 2007, when the Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired her archive. In 2011, Swiss collector and art patron Maja Hoffman purchased a complete set of printing proofs made by Selkirk; all 454 prints are on display now for the very first time in “Diane Arbus: Constellation” at the recently opened Luma Arles. Curated by Matthieu Humery, the show is the largest presentation of Arbus’s work to date: a dizzying installation that allows viewers to encounter her photographs without interpretation and chronology. Below, Selkirk reflects on his relationship with Arbus, the Luma exhibition, and Arbus’s legacy one hundred years since her birth.

I FIRST MET DIANE ARBUS in 1970 while working as an assistant for Hiro, who shared a studio with Richard Avedon. There was a good lunch at Avedon’s studio every day and she and [art director] Marvin Israel would frequently show up for a free meal. I met Marvin and Diane there just because we happened to be in the same space. By coincidence, Hiro had been given the first Pentax 6×7 camera to arrive in the United States from Japan, and he agreed to lend it to Diane. It was an enormous 35-millimeter-style single-lens reflex camera, and it allowed her to relinquish the impact of her presence on her subjects and free herself from the role of the collaborator in order to return to being simply a witness. I showed her how to use it, load it, and operate it. Diane subsequently started calling me occasionally for technical advice on jobs and we conversed periodically.

In 1970 Diane had published her portfolio “A box of ten photographs,” planned as an edition of fifty, of which she had made eight and had sold only four at the time of her death [two editions were sold to Richard Avedon, one to Jasper Johns, and one to Harper’s Bazaar art director Bea Feitler]. Henry Geldzahler, then at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, having seen the “box of ten,” took Philip Leider to see it and meet Diane at her apartment. Leider, who had previously ignored the medium, immediately decided to feature the photographs in Artforum, where it appeared on the cover and on five inside pages of the May 1971 issue. This marked a major turning point—not so much for Arbus, but for the medium of photography itself.

View of “Diane Arbus: Constellation,” 2023, Luma Arles. © The Estate of Diane Arbus Collection Maja Hoffmann / Luma Foundation. Photo: © Adrian Deweerdt.

I left Hiro’s studio in the summer of 1971 for Europe. I remember I was in Paris, and Avedon suddenly materialized out of nowhere. Diane had committed suicide and he’d come to pick up Doon [Diane’s elder daughter], who had been working with him at the time. I sent a postcard to Marvin and said, “I’m going to be back in New York in the fall; if there’s anything I can do to, I’d love to be involved in any efforts to memorialize her.” When I got off the plane in November, they were all waiting there for me because nobody else was available to print. I just happened to be the right person in the right place at the right time.

Replicating Diane’s printing process was a challenge. There’s no such thing as a quintessential “Arbus” print. That’s the point; they were always different from one another. On the other hand, she knew exactly what she needed in order to get the results she wanted, but she knew nothing about technique and relied on her then husband, Allan, for guidance in that department. For example, in New York there were probably a hundred different kinds of black-and-white film you could buy. The Adox films she had been using that she liked had been discontinued, and similar Agfa films were available only in Europe. Marvin Israel arranged for his gallery in Hannover to ship it from there. Due to the nature of this film combined with the Portriga Rapid paper she was using and the darkroom recipes Allan had designed for her, her prints always wound up being lush and rich although they didn’t follow any of the usual rules. I mean, she just didn’t know what the rules were and didn’t care. Allan designed the formula for her so that she wouldn’t have to think about what she was doing when she was taking the pictures. The image would always be salvageable regardless of the exposure.

Diane Arbus, Blonde girl with shiny lipstick, N.Y.C. 1967, 1967. © The Estate of Diane Arbus / Collection Maja Hoffmann / Luma Foundation.

Being invited to speak at Les Rencontres d’Arles in conjunction with “Diane Arbus: Constellation,” I realized many things that in fifty years had never really dawned on me. One of those things was Arbus’s unique and extraordinary capacity to essentially disappear in the situation of taking a portrait. In my experience as a photographer, and with every other photographer I’ve ever considered or had a conversation with, you go to take a picture of someone, and you are going to do something. Diane was going to push the button at a certain point, but mostly she was going to just meet someone. She was someone who to her core was absolutely enthralled to know what made people tick. That was her thing. She was interested in people, and it was completely sincere. There’s no judgment in the work. It’s powerful to pay attention to someone and to be paid attention to. A photograph she took that originally horrified me wound up changing my life because it forced me to face the fact that it was me looking at the image who was making the judgment. The photograph was not saying, “Look at this person with whatever their problems might be,” or presenting life as inevitably grim. She was saying, “This is a photograph of a person that interested me—and don’t you find them fascinating?” She’s providing questions for you to consider, not a justification for your response.

Seeing “Diane Arbus: Constellation” was literally revelatory for me. And it’s not just the breadth of the exhibition, which is the first time one has been able to go into a single room and see this many photographs by Arbus at once. The brilliance of the installation is that it’s completely unguided. You can wander and come across photographs that you have never seen before and see ones that you have, finding your own unique pace. You see in the exhibition that Diane really did want to photograph everybody, and this is the nearest she got to it.

— As told to Rose Bishop

Some parts of this interview were drawn from a public conversation between Selkirk and Darius Himes in Arles earlier this month.

ALL IMAGES