Do you like math? Well, many of us might have had some problems with it when we were in school (I, for one, had many!) and got fed up with it. So when I went to study art history I was surprised to see how closely art and math are linked. Do you doubt it? If so, stay with me and I’ll show you a little of this fascinating relationship.

As a teacher at a high school, I see how much teenagers struggle when studying calculus. In order to help them, together with the math teacher, I offer an elective course called “The Art of Mathematics”. (Okay, it was not a very creative name, I know.) Just as I felt when I began studying art history, the kids were also surprised to learn that many artworks they knew had fundamental mathematical references.

The relationship between art and math is older than we think. In pre-Columbian cultures, for example, there are many artworks (actually, aesthetic artifacts) that demonstrate knowledge of geometric patterns. However, this connection became more apparent during the Renaissance, when artists realized that basic notions of mathematics such as perspective and symmetry would make artworks more realistic.

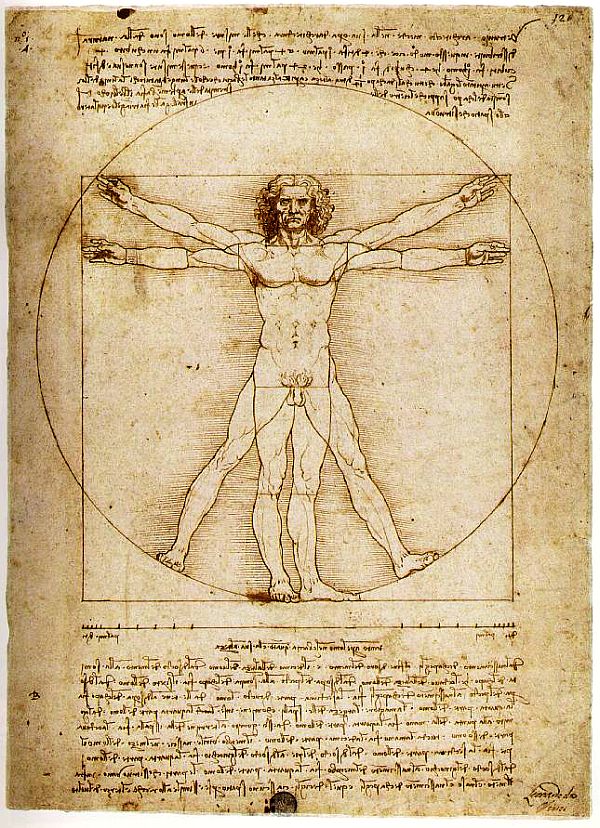

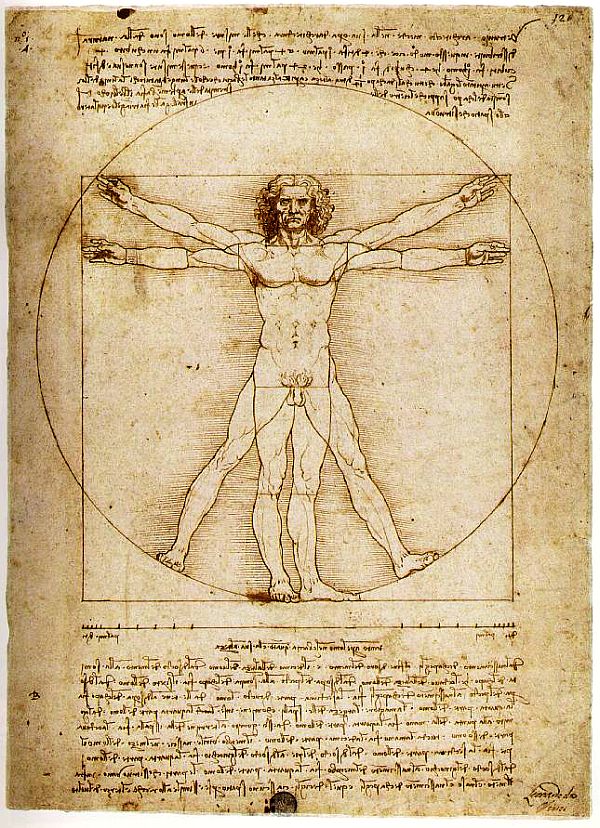

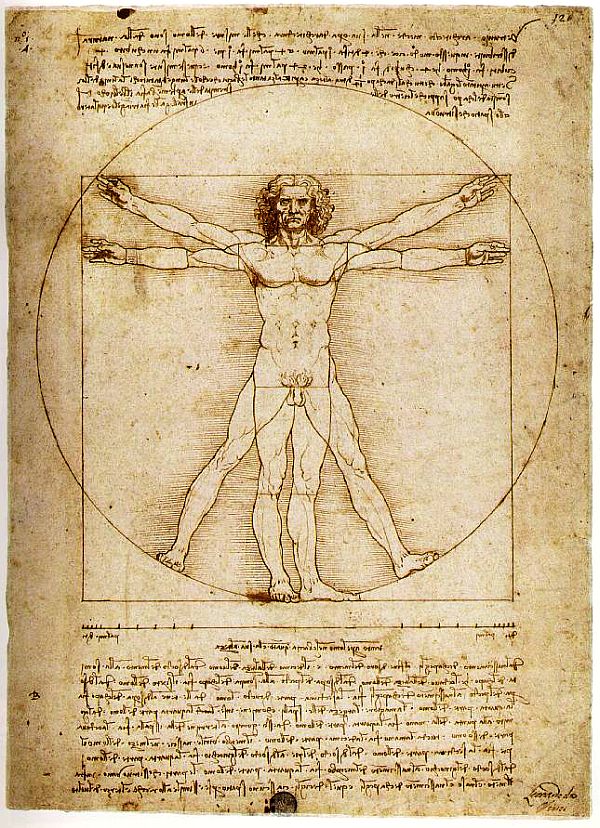

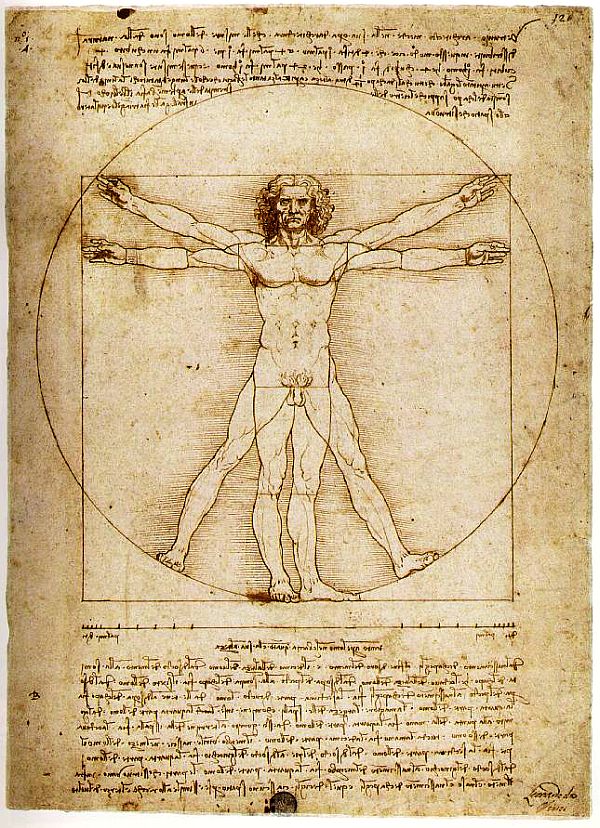

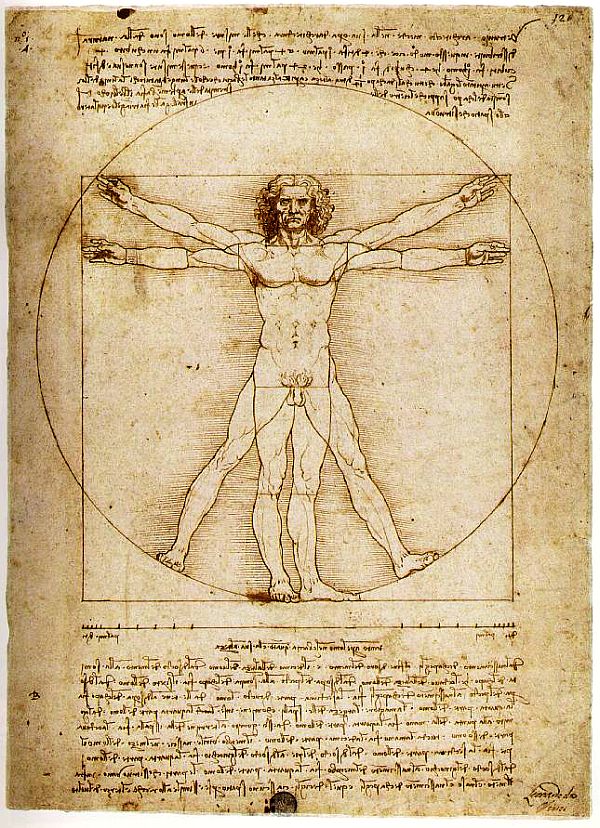

One of the most significant works in this sense is actually a study. In 1490, Leonardo da Vinci put on paper the concept of proportion conceived by Vitruvius, a Roman architect of the first century CE. In this sketch, which is one of the most celebrated works by da Vinci, the artist used mathematics to elaborate the ideal proportions of the human body. According to his calculations, the measure of the length of the open arms of a man is equal to his height, for example.

da Vinci carefully drew the man, known to us as Vitruvian Man, and placed him within two well-known geometric shapes, a circle and a square, a composition that is noteworthy, considering the structure of the drawing.

Have you heard of the Golden Ratio? Also known as Divine Proportion, this is a real irrational algebra constant that has an approximate value of 1.618. This constant (as the name implies, something fixed, an opposition to the concept of variable) is represented by the Greek letter φ. It is a tribute to an artist, the sculptor Phidias, who used this proportion to design one of the most well-known architectural projects of Antiquity: The Parthenon.

The golden ratio is a pattern that repeats itself in nature. That is why it is so fascinating and celebrated by many Renaissance artists who wanted to revive the ideals of Antiquity but at the same time, they also wanted to ground their art in the scientific evidence. Mona Lisa, another masterpiece of da Vinci, presents the golden proportion in the face and also between the neck-head ratio, which means that the ratio between these parts is 1.618. This is due to da Vinci’s interest not only in anatomy but also in mathematics.

The relations between art and math were not only evident in the Renaissance. Modern Art was a fertile field for artworks that were in some way linked to calculations. For example, Wassily Kandinsky, best known for his abstract artworks and for being a Bauhaus teacher, was one of the painters who used mathematics in his creations.

In his most abstract works, Kandinsky used many mathematical forms including concentric circles, open and closed lines, and triangles. Geometry, in particular, was an element of interest to the artist. This was not surprising considering that the Bauhaus sought precisely to be a school of art and architecture that broadened the idea of art and showed its many possibilities. Therefore Kandinsky’s interest in mathematical elements makes total sense.

However, Kandinsky was not the only artist interested in the artistic possibilities of geometric abstraction. Around 1930, the artist Piet Mondrian produced some compositions that gave rise to Neoplasticism, the avant-garde movement that sought to present a new image of art. In laying the groundwork for neoplasticism, Mondrian also used mathematical concepts to arrive at the conclusion:

“I concluded that the right angle is the only constant relation and that through the proportions of the dimension one could give movement to its constant expression, that is, to give it I exclude more and more from my paintings the curved lines, until finally my compositions consisted only of horizontal and vertical lines that formed crosses, each separated and detached from the others (…) I began to determine forms: vertical and horizontal rectangles like all forms, try to prevail over each other and must be neutralized by composition. Ultimately, rectangles are never an end in themselves, but a logical consequence of its determinant lines which are continuous in space and appear spontaneously when the cross is made of vertical and horizontal lines. of suppressing the manifestations of planes as rectangles reduced the color and accentuated the lines that bordered them.”

Also, the American painter Jackson Pollock, one of the best-known painters of abstract expressionism and one of the most controversial modern artists, linked art and mathematics. In the 1990s, American physicist Richard Taylor of the University of Oregon noticed in Pollock’s painting a relation to the geometric model of fractals. Fractals are, by definition, figures of non-Euclidean geometry. Generally they refer to a complex geometric structure whose properties are repeated on any scale.

How are the fractals linked to Pollock’s painting? Pollock used a drip technique in his paintings which makes his work seem random. Apparently, we could not be more wrong. Taylor divided the works into squares of various sizes, ranging from 1cm to almost 5m, which showed that actually, the geometric pattern repeats. Moreover, while measuring the fractal dimension of the works, Taylor noted that the more Pollock worked on this technique, the greater the values.

Well, I could go on writing examples of flirting between art and mathematics indefinitely because somehow they will always find each other. I hope that if you, like me, had problems with math, you now become a little more friendly with the calculations hereafter.