In my first Moments in Art History video, I talked about American Gothic, one of the most iconic paintings in American history. Whistler’s Mother is another American icon, although it was painted overseas in London.

The piece especially gained popularity in the United States during the Great Depression, when it was featured on a postage stamp along with the words “In memory and in honor of the mothers of America.” Just a few years later, in 1838, an eight-foot-high statue based on the painting was erected as a tribute to mothers by the Ashland Boys’ Association in Ashland, Pennsylvania. Since then, the painting has appeared in too many advertisements, television shows, and films. It’s even been called the Victorian Mona Lisa.

But like many of the most famous works of art in history, it didn’t garner praise immediately, and when it did receive recognition, it wasn’t really the kind Whistler was looking for.

Whistler painted the piece while his mother was living with him on Cheyne Walk in Chelsea, London. Legend has it that Anna Whistler became the subject of the painting when Whistler’s intended model couldn’t make the appointment and that she sat for the painting because she couldn’t stand for a long period. Still, we don’t know Whistler’s original intent for the piece.

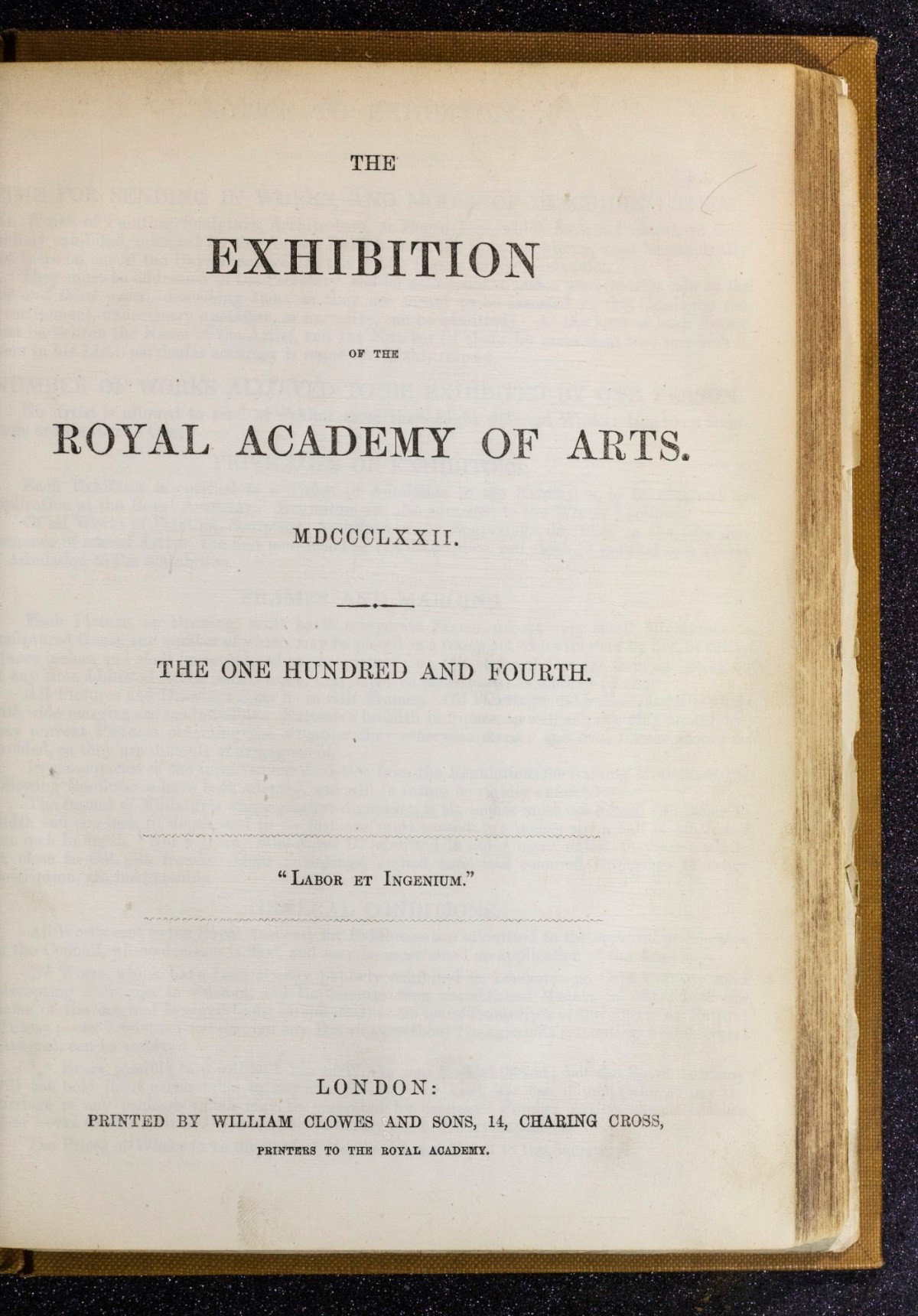

Whatever the case, the painting was displayed in the 104th Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Art in London in 1872 after nearly being rejected. Whistler already had a shaky relationship with the British art world, and the criticism the piece received only increased his frustration. As a result, it was the last piece he ever submitted to the Academy.

Whistler had titled the piece Arrangement in Grey and Black. Still, the academy added the subtitle Portrait of the Painter’s Mother, apparently unimpressed by Whistler’s attempt to present a portrait as something other than a portrait. From this subtitle, the painting got the nickname Whistler’s Mother.

After viewing the piece, British historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle sat for a similar painting, which would be titled Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 2.

The painting of the artist’s mother began to attract favorable attention when it was acquired by the French government and shown in Paris’s Musée du Luxembourg.

Of course, Whistler was thrilled with the painting’s new home, seeing it as a “slap in the face” to the London art scene that had disrespected the piece.

As a major proponent of “art for art’s sake,” Whistler likely would have been less thrilled had he known that the piece would become so famous for its maternal subject.

Confused by the public’s insistence on calling his painting a portrait, Whistler wrote in his 1890 book The Gentle Art of Making Enemies, “Take the picture of my mother, exhibited at the Royal Academy as an ‘Arrangement in Grey and Black.’ Now that is what it is. To me, it is interesting as a picture of my mother, but what can or ought the public do to care about the identity of the portrait?”

As it turns out, we care a lot, and as a result, the piece has become one of the most famous works by an American artist outside the United States. It has been exhibited several times in the United States, spending time in the National Gallery of Art, the Detroit Institute of Arts, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and several other American art museums. The piece is currently back in France at the Musée d’Orsay.

James McNeill Whistler was born to Anna McNeill Whistler and railroad engineer George Washington Whistler in Lowell, Massachusetts. However, he would later claim St. Petersburg, Russia, as his birthplace, saying, “I shall be born when and where I want, and I do not choose to be born in Lowell.”

The family did move to St. Petersburg when Whistler was a child. His father had been offered a position by Nicholas I of Russia to work on the St. Petersburg-Moscow railroad.

Whistler was a moody child, but his parents found that drawing calmed him and allowed him to focus. He began taking art lessons early and enrolled at the Imperial Academy of Arts

when he was only eleven.

The young artist followed the traditional curriculum of drawing from plaster casts and occasional live models and reveled in the atmosphere and art talk with older peers. A few years later, he met well-known Scottish historical painter Sir William Allan, who told Whistler’s mother, “Your little boy has uncommon genius, but do not urge him beyond his inclination.”

This advice turned out to be pretty prophetic. After Whistler’s father died of Cholera, the family returned to the United States, where Anna Whistler sent her son first to Christ Church Hall School in the hope that he would become a minister and then to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Neither went

very well. At West Point, Whistler constantly defied authority, spouted sarcastic comments, and earned poor grades.

He claimed to have finally been dismissed for a spectacular failure on a chemistry exam where he was asked to describe silicon and began by saying, “Silicon is a gas.” As he himself put it later, “If silicon were a gas, I would have been a general one day.”

However, during his studies there, he did have the chance to study drawing and mapmaking with Robert W. Weir, which came in handy after Whistler’s dismissal from West Point when he took a job as a draftsman. He found the job boring, leading him to pursue fine art seriously.

As you might have guessed, based on what happened with Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, Whistler’s West Point misadventures were not the end of his attitude problems. After a permanent move to Europe and time studying in France, he settled in London, where he spent almost as much time making enemies as he did painting, butting heads not only with the Royal Academy but also with several prominent English figures, from Oscar Wilde to John Ruskin.

He also struggled financially and had a string of mistresses before marrying Beatrice Godwin in 1888. She eventually became ill and succumbed to cancer, and Whistler himself died at 69 in 1903.

Along with Whistler’s Mother, some other famous works the artist produced include Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl, and Nocturne in Black and Gold. The artist often used musical terms to title his work, finding a connection between the visual harmony he created and the sonic harmony in music.

James McNeill Whistler was a controversial and complex figure, but there is no denying his talent as an artist. His most famous work, Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, better known as Whistler’s Mother, has become an icon of American art, and its story is as interesting as the painting itself. Whether you love or hate his work, there is no denying that Whistler was a master of his craft, and his legacy continues to live on through his art.

What do you think of James McNeill Whistler’s work? Do you have a favorite painting by Whistler? What do you think of his Mother’s portrait? Do an artist’s intentions for a creation matter? Share your thoughts in the comments below.