Early Life

David Brown Milne was born on January 8, 1882, in rural Ontario, Canada, near Lake Huron. The youngest of ten children, he showed a keen interest in art from a young age. When he went to high school, only the second of his family to do so, his favorite subject was botany. This is likely because these classes were mostly spent drawing plants.

As a young adult, he briefly worked as a teacher in a country school not far from his family’s farm. During this time, he was also taking a correspondence course in art from a school in New York. In 1903, at the age of 21, he decided to move to New York City to pursue a career in illustration. Milne enrolled at the Arts Students League there and studied full-time for the next two years. He also took a year of night school after that.

Move to New York

In 1906, Milne set up a studio with fellow student Amos Engle, where they produced illustrations for magazines and painted showcards for shop windows. The pair also took painting holidays together in upstate Pennsylvania and New York. Soon thereafter, they began exhibiting their watercolors from these trips. At the time, galleries in New York City were showcasing revolutionary works coming out of Europe—Milne took particular interest in the Impressionists.

In reaction, he created his own brand of modernism. In 1912, his work was some of the most radical among American artists of the time. For example, the Armory Show of 1913 accepted five of his works. This was a much larger selection than most other domestic artists—Edward Hopper only had one! During this period, Milne courted and eventually married May Frances Hegarty, better known as Patsy, in 1912.

Reconnecting with Rural Life

Looking to reconnect with Milne’s rural roots, the couple moved to the hamlet of Boston Corners in 1916. There, they were able to rent a small cottage for just $6 per month. Milne was quite the handyman and farmer. He renovated the cottage to make it suitable to live in during the winter, they planted a substantial vegetable garden, and they even raised chickens and a duck for meat and eggs. They lived almost completely self-sufficiently.

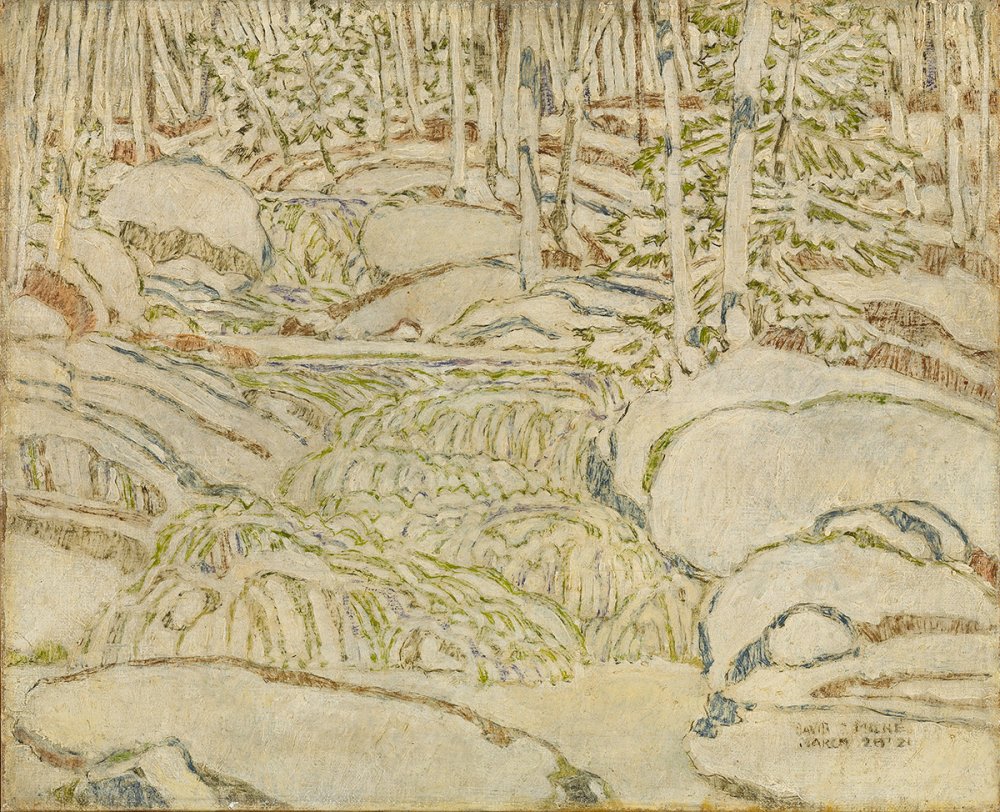

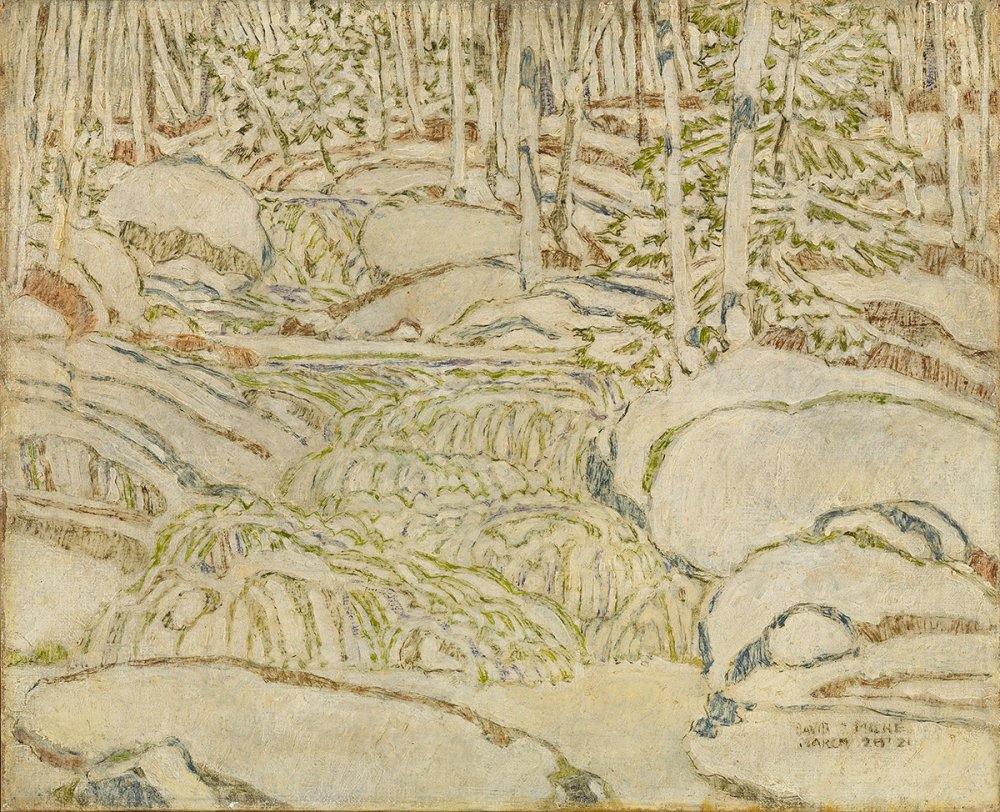

During this period, Milne continued to work in watercolors but also experimented more with oils. He used a very interesting yet stripped-down color palette featuring unusual color combinations and often restricted the number of colors to just three or four at a time. He was greatly inspired by his surroundings in Boston Corners, producing many landscapes as well as images of the village and its surroundings. Milne became very regimented in his work. He devoted time to go for walks in search of new subject matter, allotted time for painting, and time to review and analyze the day’s work, looking for ways to improve on future pieces.

The War Years

In 1917, Milne enlisted in the Canadian Army and went to Toronto, Ontario, for basic training in early 1918. From there, he was part of a force sent to the eastern townships of Quebec to assist in quelling conscription riots and rounding up deserters. Eventually, he was shipped to England, but the war ended while he was still in quarantine in Wales.

Milne discovered the Canadian War Memorials Fund by accident, and they engaged him as a war artist to depict places in England where Canadian forces were stationed. The following year, he was sent to paint the aftermath of the battlefields in France and Belgium. In all, he made 109 war paintings, all of them watercolors, and they are some of his most powerful works. Furthermore, this experience increased his reliance on drawing and the importance of line and shape in his subsequent works.

Return to America

Milne returned to Boston Corners in 1919, immediately getting into the rhythm of producing a steady stream of paintings. He also started typing up detailed notes on each work, cataloging them, recording his intentions, assessing his performance, and determining whether he felt each piece succeeded or failed. Sadly, this was not to last.

Milne took a pause from painting in 1920 and worked intermittently in the years to follow as he and Patsy held down odd jobs at resorts in the area. Their relationship became increasingly strained. Throughout the 1920s, Milne worked very sporadically, giving up watercolor altogether. He did some experiments with drypoint etching with the intended goal of making them with multiple colors. However, when he did get around to art, his works were as strong as ever.

Return to Canada

In the spring of 1929, Milne moved back to Canada alone, settling in Temagami, a village in northern Ontario. He recommitted himself to painting, working exclusively in oils and creating almost 40 works in the following months. That fall, he moved to Toronto, and Pasty reluctantly joined him. Not long thereafter, they moved to the village of Palgrave, northwest of Toronto. Again, they were in search of a lower cost of living and the rural environs Milne loved so much.

They spent the next three years in Palgrave, during which Milne produced over 200 oil paintings—mostly landscapes but also some still lifes. Through these works, he developed a system of painting that used white, grey, and black to form the structure of the image, with color used sparingly and sometimes only as accents. This was also the height of the Great Depression. Money was very tight, and yet Milne prioritized affording painting supplies over life necessities. Expectedly, this took a great toll on his relationship with Patsy, and the pair legally separated in 1933.

Milne Gains Patronship of the Masseys

Milne relocated yet again to Six Mile Lake, Canada, where he bought a plot of land with the intention of building a cabin, but didn’t get beyond a makeshift lean-to where he would live and work for the next six years. Once settled, he approached prominent Canadian patrons Vincent and Alice Massey with an offer to exchange all of his accumulated works (about 1,000 paintings in all) for enough money to sustain him for the next few years. They agreed to buy just 300 works for $5 each.

Contrary to Milne’s wishes, they quickly partnered with the Mellors Galleries in Toronto to resell the paintings with promises to share the profits with Milne once they had recouped their initial $1,500 investment. Sadly, Milne saw little of this money due to the large commission taken by the dealer at the gallery. However, the paintings sold very quickly.

The Masseys also bought all of Milne’s production from 1935 to 1936 at an even lower rate per painting, and due to a dispute, they ended their relationship with the gallery abruptly in 1938. Some of the unsold paintings were returned to Milne. Meanwhile, the Massey’s walked away with almost 350 paintings. They would later sell off most of these in 1958 for a large profit that was not shared with Milne’s estate or dependents.

Life in Toronto

Despite their stinginess, the patronage of the Masseys was a boon for Milne. The exhibitions they arranged in Toronto brought the artist much attention and subsequent sales. He also gained the patronage of another collector and the director of the Picture Loan Society, Douglas Duncan, who would be Milne’s agent and dealer for the rest of both their lives. Milne took new directions in his work, returning to watercolors in 1937 and exploring some fantasy and religious subjects. His output in oils, meanwhile, dropped off significantly and is almost non-existent in his later works.

In 1938, Milne met and fell in love with Kathleen Pavey, a nurse who was half his age, and he moved to Toronto in 1939 to be closer to her. Over the next two years, he explored more urban subjects, including the parliament buildings, churches, breweries, houses, and apartment buildings. Kathleen became pregnant, and the pair decided to move to Uxbridge, Ontario. She was worried about the scandal and social stigma of having a child out of wedlock. At the time, Kathleen was using Milne’s last name, but he had never formally divorced from Patsy. Their son was born in May of 1941.

Later Years and Death

Milne settled in and worked steadily for the next seven years, despite wartime shortages making sales and finding quality supplies difficult. His watercolors of the 1940s and 1950s include more fantasy pictures featuring a larger spectrum of colors than his earlier works. He was also inspired by biblical stories for children, such as Noah’s Ark.

Never one to settle for too long, Uxbridge lost inspiration for him, and in the fall of 1947, he went to Baptiste Lake near Algonquin Park in search of a new place. Again, he found a plot of land where he built a cabin. He was 66 years old when he started its construction and almost finished it over the course of a summer. However, his health was beginning to deteriorate, and he worried about having enough money to support Patsy, Kathleen, and their son, David Jr. On November 14, 1952, Milne suffered a stroke that took away his ability to paint, and he died in hospital on December 26, 1953, after months of suffering from subsequent strokes and trying to recuperate.

Reflections

While David Milne was a contemporary of Canada’s better-known Group of Seven, he preferred to work independently. He even explored similar themes to the Group of Seven through his landscapes. However, his style is so unique, so individual, that it would be difficult to confuse his pieces with those of the Group of Seven members. Would he be better known today had he joined the group? Would working and exhibiting with others have had an impact on his visual style?

Some artists develop a style early on that remains with them for the rest of their lives. This is not so with Milne. His style changed constantly throughout his life, along with his preferred medium to work in. He also never settled for long in any one place. It seems that with each subsequent move, there is a slight shift in his style. When all these subtle changes are added up, his later works appear completely different from his earlier ones. If he hadn’t moved around so much, would his style have become stagnant as well?

For Milne, art was the most important thing. He prioritized it over everything, even his personal relationships. While this led to the downfall of his marriage, the sheer number of works he produced at such a high quality over the span of his career is incredible. If his priorities had been different, would he have been able to create so many amazing pieces of art?