What is it with artists and sausage dogs? Andy Warhol had Archie the dachshund who’d accompany him to art openings and dined with him at Ballato’s, occasionally hidden under a table napkin to escape the eyes of any over-zealous Health & Safety inspector.

Archie was soon joined by another dachshund, Amos, who quickly made himself at home in a series of Warhol’s mid-Seventies paintings.

Meanwhile, Picasso adopted and found a muse in Lump, a friend’s dachshund, painting him on a lunch plate in 1957, and replacing Velazquez’s profound hound with the pampered pet in 15 of the studies he made of Las Meninas, later that year.

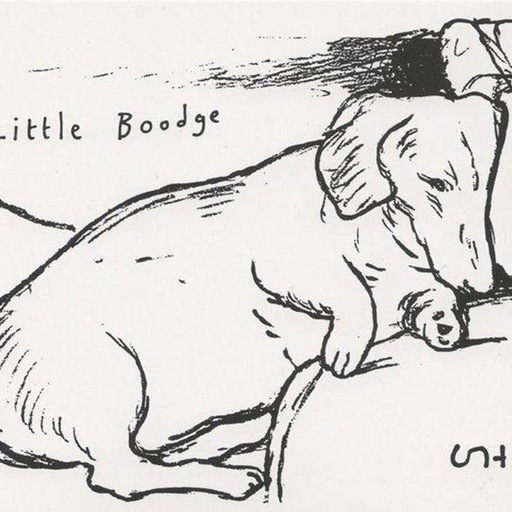

But it was English painter David Hockney who most successfully highlighted the connection between artist and four-short-legged-friend, with the drawings, paintings, and prints he made of his two dachshunds, Stanley and Boodgie, who shared the painter’s California home during the late Eighties and Nineties.

DAVID HOCKNEY – Stanley and Boodge, 23rd September, 1993, 1993

Hockney would set up easels around his Montcalm Avenue house in the Hollywood Hills in order to paint the dogs quickly, easily, and in different poses; “in a way only the owner could,” he said.

The artist had often resisted the allure of strangers in favor of painting family members or close friends, these intimate portrayals of his dogs was part of that process. Both dogs had distinct personalities and Hockney understood them well.

“Stanley will follow me everywhere, unless it is raining, or someone is dispensing food. Boodgie is more of a loner,” he said in 1995. “They live very comfortably, occasionally going to the beach, and have only two interests as far as I can see: food and love, in that order.”

DAVID HOCKNEY – Boodge and Stanley, 30 May 1994, 1995

Stanley and Boudgie became the focus of an impressive 1995 show, Dog Days, at Yorkshire Salts Mill, in Bradford, UK, which featured 45 paintings. The previous year, Hockney had exhibited images of the two dogs at the same venue as part of a show of new drawings.

Hockney’s ‘dog wall’ was pretty much a glimpse into his life at the time, with the artist’s personality and quick hand, evident along with his obvious affection for Stanley and Boodgie.

“I was painting a lot of big, abstract, pictures at the same time, internal worlds. These are the external world because it was the one immediately in front of me. I rather enjoyed that contrast,” Hockney said. “I notice the warm shapes they make together, their sadness and their delights. They are a wonderful subject – two little creatures that you love. We see images of hell lots of times. Heaven is much harder to picture.”

Hockney started the painting process by sketching the dachshunds, though they were not always cooperative subjects. If he got up to get more sketch paper, the dogs would get up and follow him.

DAVID HOCKNEY – New Drawings, 1994

“I usually had 20 minutes or half-an-hour, depending on what position they were in,” he said. ”They are all done quite quickly. It was very intense, and I was quite tired by the end. It was the only perceptual painting I have done for a long time, meaning that I was painting something that was absolutely in front of me.”

Domesticated around 20,000 years ago, dogs’ relationship with humans was depicted even in cave drawings. In Titian’s Venus of Urbino a loyal dog sleeps soundly in a silent show of allegiance, and woodblock prints of dogs predominated in Edo and Meiji-era Japan.

Both Leonardo da Vinci and Sir Edwin Landseer placed dogs at the center of artworks; Lucian Freud, famously painted Pluto, his whippet. A painting of Thomas Gainsborough’s favorite dogs Tristram and Fox, hung above the portraitist’s fireplace.

“Dog portraits can tell us not only about our pets, but about ourselves, our values, our moral leaning, our social standing,” says Alexander Collins, assistant curator of a recent show of dog artworks, which prominently featured Stanley and Boudgie, at the Wallace Collection, London.

Hockney’s initial motivation for painting his dogs was prompted by a somewhat anguished series of events. Having lost several friends in the Eighties and Nineties to AIDS, Hockney was devastated when his close friend, the American curator Henry Geldzahler succumbed to liver cancer in 1994. He told the LA Times writer Barbara Isenberg, “I felt such a loss of love I wanted to deal with it in some way. I wanted desperately to paint something loving.”

“I realized I was painting my best friends, Stanley and Boodgie. The subject wasn’t dogs but my love of the little creatures. They sleep with me; I’m always with them here. They don’t go anywhere without me, and only occasionally do I leave them. They’re like little people to me.”

In the years immediately following his Yorkshire exhibition, Hockney set up a studio to make prints of his dog works, working with etching and aquatint to create multiples by drawing directly on to plates to replicate the spontaneous approach of his 1995 paintings.

The prints picture each dog asleep on a chair cushion, or basket – apart or together – the cushion apparently employed by Hockney, as a framing device.

Stanley and Boodgie may be gone but they live on in the prints, paintings, and posters from those Nineties exhibitions. And as Hockney celebrates his 86th birthday in Normandy, northern France, this weekend he’ll be doing so with his current four-legged friend – a white with brown spots crossbreed called Ruby. Take another look at our Stanley and Boudgie prints and original Nineties exhibition posters, alongside some other great works by David Hockney on Artspace.

DAVID HOCKNEY – Dog 38 and Dog 43 (set of 2), 1995